Local News

The Scarecrow of Hazard Mill

Under the Black flag – Shenandoah Valley 1864

There has never been a more wretched hive of murder and villainy than existed in the vicinity of Front Royal in the fall of 1864. Union Brig. General Wesley Merritt described the area as a “…paradise of bushwhackers and guerrillas.” Soldiers and civilians were murdered everywhere in cold blood while either traveling along the roads or in their homes.

From August through October of 1864 a host of demons descended upon the Front Royal community. Federal and Confederate Raiders roamed the countryside, essentially operating under the black flag of anarchy, giving no quarter. Each side executed prisoners and dragged them through the streets. Meanwhile, deserters and marauding bands of outlaws flourished in the mass disorder, and rape and looting went unchecked for months. Refugee women and children trudging northward from burning farms with all their belongings were easy prey for bushwhacking outlaws.

“FIRE IN THE VALLEY, The Berryville Wagon Train Raid” art by John Paul Strain.

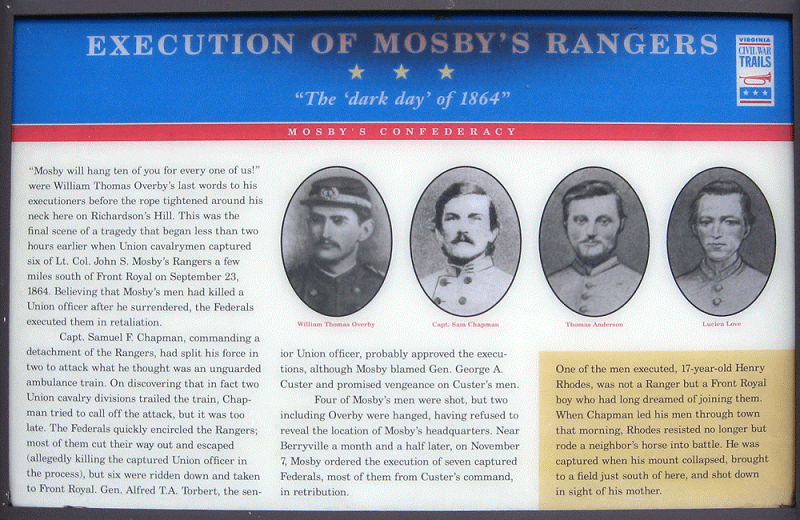

In one of the most heinous instances of brutality, the towns people of Front Royal looked on in horror, as Federal cavalry dragged six of Mosby’s Raiders through the town – their band playing the death march. Two of the Rangers, David Jones and Lucian Love, were dragged out of the procession, lined up and shot in front of a church and left to die. While that was occurring, another Confederate horseman, Thomas Anderson, was dragged by horse through the streets to a nearby tree and shot in the head. His hands still tied.

A couple more cavalrymen rode through Front Royal’s main streets, dragging 17-year-old civilian Henry Rhodes behind them. Young Henry Rhodes was not a member of Mosby’s Rangers. He was a 17-year-old resident of Front Royal that had long dreamed of riding with Mosby’s men. He had remained at home to support his widowed mother and a younger sister. When Mosby’s Rangers rode through the town on their way to attack a Yankee ambulance train, Rhodes could not resist and mounted a neighbor’s horse and joined his heroes. His horse, however, collapsed during the race toward Chester Gap, and the teenager was overtaken by the Federals.

Henry Rhodes was paraded by his home that same morning, his arms lashed to the saddles of two Union cavalrymen, who dragged the youth up Chester Street. When Mrs. Rhodes saw her son, she ran screaming to him, hugged him and pleaded with the Yankees to spare his life. One of the Yankee cavalrymen brandishing a saber, threatened to behead both mother and son. A young man’s dream had become a family’s nightmare.

The troopers were men from Custer’s Michigan brigade. When the procession passed in front of young Henry’s mother, the cavalrymen stopped and dismounted. The sergeant in charge untied the ropes and Rhodes stumbled and fell. His wailing mother pleaded for mercy as the town’s people gathered along the fence railings to watch. The inflamed Union soldiers mounted on their horses taunted the prisoner. The cavalrymen surrounding the sergeant cheered and yelled “shoot him Cline” to the red bearded sergeant standing over the hated Mosby criminal.

An eyewitness account told of Henry Rhodes’s final seconds of life. A young girl, Sue Richardson, stated that his executioner, identified by the shouts as Sergeant Cline (later identified as Willie Cline), “ordered the helpless, dazed prisoner to stand up in front of him” while he emptied his pistol into his face in front of his mother.” The name and vision of Sergeant Willie Cline was instantly seared in the memory of that on-looker.

From the window of her house, Miss Richardson had watched. She knew Henry Rhodes and was probably close to him in age – and she never forgot his death. The scene haunted her, and she wrote in her diary: Such excitement and cruelty as never was witnessed here before … that poor Henry Rhodes should be shot in front of our door. The crowd assembled around him, then we had the pain of seeing the cavalry horses pass over him before his body was removed and left in a wheelbarrow at his mother’s door. His poor mother is almost crazy. I will not sleep until I get the name of this villain to Mosby.

The last two prisoners, William Overby and a man called Carter, were led off to be hanged by a huge and wrathful crowd of soldiers. Overby and Carter were taken to a large tree outside of town and offered freedom if they disclosed the location of Mosby’s headquarters. They both refused, and with hands tied behind their backs they were summarily hanged and left swinging for several hours. A sign was attached to Overby’s body reading, ‘Such is the Fate of All Mosby’s Gang.’ Custer’s men left them hanging to ensure all the townspeople witnessed the justice – knowing Mosby would get the message. He did.

Enraged, Mosby’s men responded by cold bloodedly shooting Lieutenant John Meigs from his horse in vicinity of Custer’s headquarters. ‘In tears, Custer wept for his unfortunate orderly, who he said was ’shot down like a dog and stripped of all but his trousers.’ A short time afterwards, Custer exclaimed, “Lookout for smoke” – and soon you could track Custer’s vengeance as ugly columns of smoke started to rise in succession as he moved up the valley. He burned down all the farms and houses in a five-mile radius.

Painting entitled, “Sheridan’s Ride” by Thomas Buchanan.

Mosby’s guerrillas followed the smoke too and mercilessly killed any Union soldiers they could find – leaving them along the roads, with throats slit or hanging from trees. No quarter was the policy adapted by all sides. The Rangers searched relentlessly for Sergeant Cline but could not find him. Before killing the unfortunates, the Rangers pressed their prisoners for information about Sergeant Cline – but to no avail. All they had was a physical description and that he was in the Michigan cavalry.

Correspondent Francis Long of the New York Herald wrote, ‘The intervening country between Harrisonburg and Winchester is literally swarming with guerrillas,’ Grant urged Sheridan to continue destroying whatever was useful for ‘if the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.’

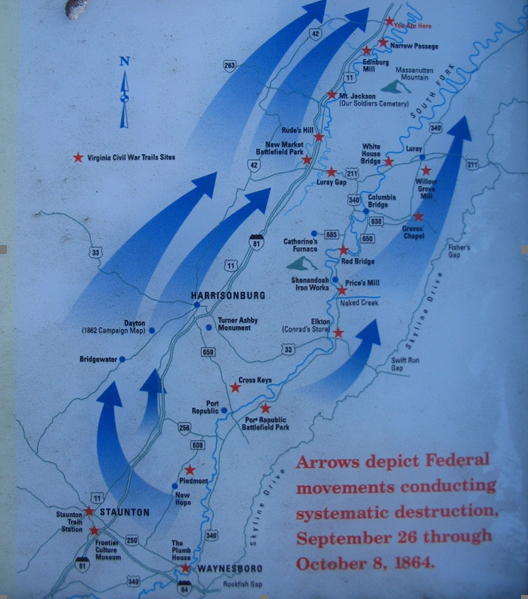

The Burning

For five days Custer tore into an 85-mile Shenandoah stretch, from Winchester to Waynesboro, burning mills, barns, houses, and granaries, destroying bridges and ripping apart railroad track. Custer exclaimed, “I will put the fear of Hell in these people.”

Mosby struck back with vengeance. On October 11, guerrillas ambushed and killed Lt. Col. Cornelius Tolles, Sheridan’s chief quartermaster, and Dr. Emil Ohlenschlager, Sheridan’s medical inspector.

Federal retaliation swiftly came on October 13, when Union Colonel William Powell hung Ranger A.C. Willis from a small tree and left him. Davy Getz met a similar fate. Getz was a mentally retarded man captured by Custer’s forces while hunting with a squirrel gun near Woodstock. Presumed to be a bushwhacker, he was marched to Harrisonburg and hung despite prolonged pleas from the residents. Vengeance begat vengeance.

When one of Custer’s ‘burn patrols’ was overrun by Mosby’s men – the Rangers lined up about 25 of them and executed them on the spot. Several more of Custer’s men were captured and hung as close to Custer’s camp as possible. Three more of Custer’s men were hanged along the side of the Valley turnpike. Hanging was slow work, so Union soldiers were often systematically lined up and shot with pistols at point blank range. The merciless killings and hangings by both sides went on for weeks.

Union devastation of the Shenandoah Valley continued into late October as Sheridan’s forces pushed the Southern army south beyond New Market.

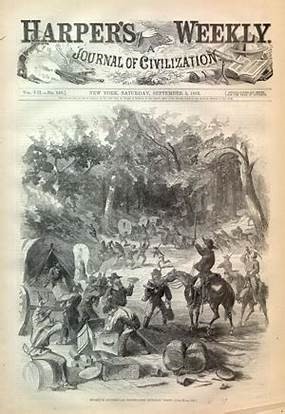

John S. Mosby Raid drawing featured in September Harper’s Weekly edition 1864.

Bands of Mosby’s men roamed both sides of the valley along with countless deserters and outlaws. They often snuck into Union camps at night using rainstorms to mask their sounds and cut the throats of anyone they found. In one such incident, a small band of raiders snuck into a Federal ‘hastily configured overnight campsite.’ The site was in disarray as it had recently fended off an attack from bushwhackers and they were low on ammunition.

After a brief firefight, the Rangers yanked all the wounded out of the wagons and sat them together in the rain under guard while they plundered the wagons. No one paid much attention to the prisoners until one of the Rangers overheard a conversation amongst the prisoners addressing Sergeant Cline. When questioned by Mosby’s men – it was clear that Sergeant Cline was with Custer’s Michigan cavalry. He also fit the description given by Miss Richardson. Alas – they had captured the murderer of Henry Rhodes.

They quickly segregated him from the rest of the prisoners and fled into the darkness with the wounded Cline in tow. Just before dawn, the small band of horsemen was spotted by Union cavalry and took flight westward down the hill fording the South Fork of the Shenandoah River towards the safety of the forest. After evading the enemy for a couple hours the Rangers forded several streams and took refuge along the west bank of the river at the site of a burnt down mill – known locally as Hazard Mill. Ironically, the mill had been owned by a Unionist that did not support the Southern cause. The site had apparently been contested during the ‘burning campaign’ as over a dozen bloated corpses and many spent cartridges still littered the area. The bodies were mostly stripped of clothing and possessions – likely the victim of deserters hiding in the hills.

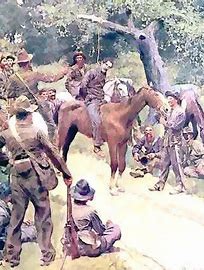

Drawing attributed as “War to the Hilt” by US National Park Service.

“They talked it over with me sitting on the horse,” by Howard Pile.

Legend has it that the Rangers coerced Cline into admitting the brutal murder of Henry Rhodes. He reportedly showed no remorse. After a little taunting of their own, the Rangers assembled everyone to watch the spectacle. Willie Cline was placed on a horse with hands tied behind his back and was hung from a tree within site of the old mill.

Aftermath: By December, the war moved eastward, and the belligerents departed the valley. The war in Virginia ended the following spring and Mosby disbanded his command shortly afterwards about 22 miles east of Front Royal. Many of his Northern adversaries headed west to fight Indians. Mosby’s principal foe, General Custer, died with all his men about 12 years later at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

After the hanging of Cline, members of Mosby’s force informed Sue Richardson of the revenge.

According to Miss Richardson’s diary dated in May 1864 (after Lee’s surrender) she’d heard stories of a Union soldier (known as the Scarecrow) still hanging from a tree near the ole Hazard Mill site. One weekend, she and others ventured out on a day trip on horseback in search of the scarecrow. She wanted to be sure it was really Cline. A local boy took them to the site. There they discovered Cline’s decayed body still swinging from the tree. “His blue blouse had faded considerable, and the crows had picked away at him clean – but it was him for sure. His ‘orange tinted’ hair billowed in the wind and his lifeless body gently drifted left and right when the breeze whipped up. As I gazed at him, I couldn’t remove the vision of Rhode’s poor mother wailing in agony on Chester Street. Cline got what he deserved. We left him swinging.”

Sergeant Willie Cline joined the list of many souls who were never accounted for during the valley war of 1864, however, few would be remembered as he was.

The story of the Scarecrow of Hazard Mill grew over the years and children would hide behind trees and watch it at night to see if it came alive. Unruly children were often threatened that the scarecrow would come for them unless they behaved. Locals used the site as a reference point for directions. The morbid site was known to most people in the area, but no one removed it from the tree. Allegedly, he continued to swing for years. The people felt they would be doing an injustice to the widow Rhodes if they cut him down. Later, stories circulated that his crumpled remains formed a pile next to the tree that bore his weight. As time passed his remains disappeared and only the legend remained. In the late 1800s, a few locals would occasionally hang a scarecrow in a tree in reference to the scarecrow stories.

The story of the Scarecrow of Hazard Mill grew over the years and children would hide behind trees and watch it at night to see if it came alive. Unruly children were often threatened that the scarecrow would come for them unless they behaved. Locals used the site as a reference point for directions. The morbid site was known to most people in the area, but no one removed it from the tree. Allegedly, he continued to swing for years. The people felt they would be doing an injustice to the widow Rhodes if they cut him down. Later, stories circulated that his crumpled remains formed a pile next to the tree that bore his weight. As time passed his remains disappeared and only the legend remained. In the late 1800s, a few locals would occasionally hang a scarecrow in a tree in reference to the scarecrow stories.

For years after the conflict the fall of 1864 was known by Valley residents simply as ‘the Burning.’ The Civil War departed the Valley, but it left permanent scars on the land, and on its residents. Hatred towards the north continued for decades until those that lived the era and their offspring had passed on.

Today, it’s difficult to find anyone familiar with the ‘Scarecrow’ legend and you wouldn’t know there was a war in the valley at all, if not for the descriptive “Civil War Trails’ signs. Many families have come and gone over the 150-plus years since the burnings. Many of the locals that lived in the valley during the war fled the area afterwards for a more promising life in nearby towns. Some places in the valley remained untenable for years. There was no livestock, no barns or houses or stores for miles in some stretches. Those that later inhabited the Bentonville area heard the hills were haunted and stayed away from the ole mill. Today, the dirt road to Hazard Mill still bears its name. The ruins of the ole mill remain but the acreage is now part of the George Washington National Forest.

Photograph taken by Lt. Colonel (Ret.) John Morgan.

There is only one residence within the National Forest near the site. The actual Hazard Mill site is owned by Lt. Colonel (retired) John Morgan and his wife Sonja. Mrs. Morgan is quick to tell you that the area is “definitely haunted” and can regale you with many tales of such. The colonel acknowledges that the area is full of energy and occasionally erects a scarecrow in October to commemorate the legend. The local Equestrian club reports that during their annual October ride through the National Forest, they occasionally see a ‘Halloween-like’ skeleton cloaked in Yankee blue hanging on the legendary hill above Hazard Mill.

Photograph taken by Sonja Morgan.

(Portions of the details of the Valley war and the story of Henry Rhodes were extrapolated from “Mosby’s Rangers” by Jeffrey D. Wert, 1990).