Looking Back

Looking Back: A Mothers Revenge – Hannah Duston

Hannah Duston was the first American woman to have a statue built in her honor, in 1874. Today, what she did to deserve it might be called, by some, a monument to an atrocity. What did Hannah do? Hannah scalped the ten Indians who had attacked her farm, dragged her from her bed, and burned her house down before taking her captive and killing her six-day-old infant.

The statue to Hannah Duston, in Haverhill, Mass. Panels around the statue base describe the incidents from Hannah’s ordeal.

Detail of the hatch-wielding Hannah

It is difficult to imagine today scalping a person. There is adhesive tissue under the dermis of the skull which must be cut and pulled off by the hair. The scalp bleeds exceedingly freely, and the instrument of destruction, especially if crude like a hand-forged iron knife, would be clumsy and slippery when wet.

And what of the revulsion one might feel at handling a dead human in this way? Had Hannah’s life prepared her for that? She was certainly used to wringing chickens’ necks, helping with the slaughter of cows and pigs. Further, she must have been rather angry when she scalped the ten Abenaki Indians who had recently been her captors. They had, after all, attacked her farm, dragged her from her bed, and burned her house. They had taken her captive, and almost immediately killed her week-old infant by bashing the infant’s head against a tree because the baby was crying. Having taken her captive, the Abenaki Indians forced Hannah and her aunt Mary to walk many miles north in March while wearing only their nightclothes. And, for all she knew, the rest of her family was dead.

Hannah and her family were no strangers to horror. She had been captured at the end of King William’s War, in an era distinguished for its savagery on both sides; many outlying British settlements—this was still colonial Massachusetts Bay—had already been plundered and burned.

This is important: When we read Hannah’s story, the context of the late 17th Century is paramount. If Hannah is to be judged at all, then we must judge her in the light of the history that preceded her, not the history, including our present day, which followed. One simply cannot fully understand any events and personalities of the past through the context of the 21st Century.

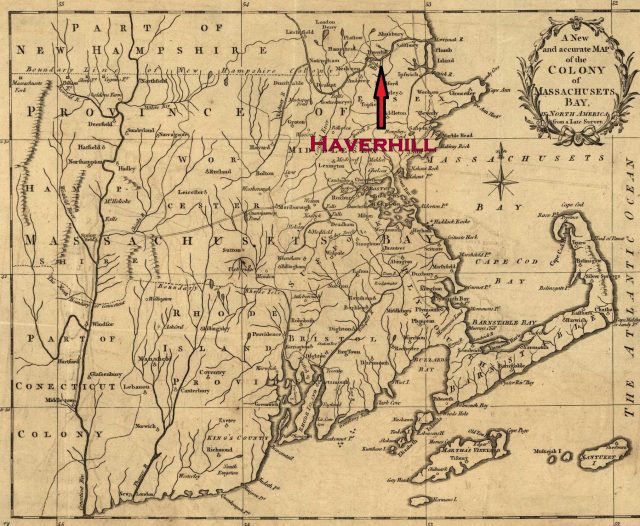

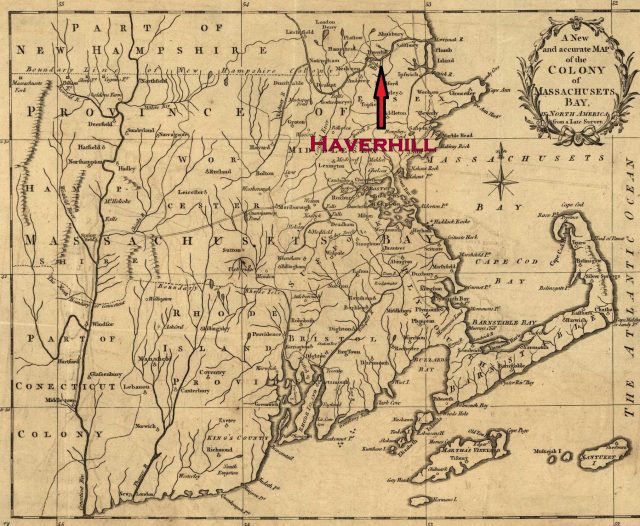

Map of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, showing Haverhill.

It was the 15th of March in the year 1697. There was still snow on the ground, though it had melted away in sunny spots from the bases of bushes and trees. To the northwest of the main town of Haverhill, in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, there were six or so buildings, surrounded by fields and meadows. This was where Hannah Duston lived in a small brick house, with her husband Thomas, a brick-maker and farmer, and their eight children. Hannah was forty years of age at the time and had just given birth six days before to her eighth child, a girl called Martha. Her capture occurred during the Raid on Haverhill by the Abenaki people from Québec during King William’s War, in which 27 colonists were killed.

On the day of the Raid, Hannah was lying in bed. She was talking with Mary Neff, her aunt, and also the local midwife. Hannah had borne a girl child just six days before. She was wearing her nightclothes and the babe was nursing well; she was a strong infant, according to Hannah later. The other children were outside playing; they ranged in age from 3 to 18. There was not much work to do in March, other than splitting wood. The fields were not ready to be plowed, and the stock had been cared for in the barn.

Thomas Duston was out in the fields at the time of the Raid. Likely he was wary, and had his gun with him, the long rifle; the previous Summer in Haverhill, four of his neighbors were killed by Indians while in their fields, picking beans. It is believed, according to documents about the Raid, that Thomas caught a movement out of the corner of his eye. Ten Abenaki Indians stepped from behind the trees in the distance. A series of shots broke the morning stillness, and Thomas leaped on his horse and galloped toward the house, screaming as he rode, “Indians! Run to the Marsh Garrison! Now!”

“Her husbands’ defense of their children against the pursuing savages”

The children dropped what they were holding and grabbed the younger ones. The walled garrison was nearly a mile away; the Indians are already close. The chances of reaching the garrison were slim. Hannah related later that Thomas rushed into the house while she was getting out of bed. Aunt Mary grabbed Martha, the infant, and ran outside. Hannah told her husband to run and escape with the other children. There was no time for any good-byes, as the Indians had just captured Mary Neff and the infant, and were apparently distracted while Thomas escaped.

The other children had run some six hundred feet, with the older ones carrying the younger children. Thomas rode up among them; his plan was to snatch up one or two of the younger children and ride away with them to save a few. The Indians were in pursuit, and Thomas stopped his horse, dismounted, and using the horse as a shield, threatened the small group of pursuers with his rifle. The Indians took cover and fired, but neither Thomas nor his horse was hit. Thomas jumped back on the horse and rode up to his children; the Indians had reloaded their guns and renewed the pursuit. Once more, Thomas dismounted and menaced his pursuers. Again the Indians fired, and again, neither Thomas nor his horse was hit. The Indians apparently gave up; there were easier spoils back at the group of undefended houses where the attack began.

“Was captured by the Indians in Haverhill the place of her nativity March 15, 1697″

The Indians did not kill Hannah and Mary. Hannah related that twenty-seven of her friends and neighbors were killed, and thirteen taken hostage. The captives were collected into a group with some twenty Indians. The victors carried things taken from the now-burning house, including a large piece of cloth torn from Hannah’s loom. Hannah was huddled beside Mary; in the ensuing confusion when she was captured, Mary had lost a shoe. With the hostages, Indians turned to the north, away from the garrison, to get away with what they had.

According to Hannah’s later statements, Aunt Mary was carrying baby Martha when she stumbled. The infant began crying, and suddenly one of the Indians grabbed Martha from Mary, and, swinging the infant by her feet, smashed her head against a tree, killing her. Hannah and Mary have pushed ahead. Hannah stated later that she believed that the Indians were annoyed by the crying. Hannah and the others traveled about 12 miles that first day, through swamps and some snow, up hills and over brooks. The Indians placed the household goods they had confiscated on the backs of the captives, making travel difficult. Hannah said that several of the prisoners are not able to keep up the grueling pace, and were taken aside and tomahawked. Their scalps were added to the collection already carried on poles or packs.

The first night, when the party stopped to rest, Hannah and Mary held each other for warmth and comfort. Hannah said they slept that night with a piece of rawhide pressed over their torsos and tucked under them.

For fifteen days they traveled north. Finally, near present-day Boscawen, New Hampshire, north of present-day Concord, the Indians conducted the party to an island in the Merrimack River at the junction of the Contoocook River to rest for a few days. It was easier to keep watch from the island for any pursuing militia and other Indian raiding parties.

Hannah related later that the Indians Hannah and Mary were with prayed three times a day in Latin, having been converted by the French to Catholicism. Hannah’s immediate captor told her in broken English that he had lived for some years with a preacher named Rowlandson he had captured, and been taught to pray in the English. He did not allow Mary and Hannah to pray openly; they had to do it in secret while gathering wood or water. Years later Hannah said, in her belated Confession of Faith: “I am Thankful for my Captivity, ’twas the Comfortablest time that ever I had; For In my Affliction God made His Word comfortable to Me.”

After another two weeks, the Indians split up. Hannah and Mary were parceled out to a group whose eventual destination, Hannah was able to determine, was a place called St. Francis in Canada. This smaller group consisted of two warriors, three adult women, and seven children. Also among them was a 14-year-old English boy named Samuel Leonardson, taken from Worcester, in the western part of Massachusetts Bay, some 18 months before. He has been with the Indians so long he had learned to speak their language, and so was considered almost a member of the tribe. Despite not trying to escape in all that time, by one account, Samuel was moved by the plight of these new captives, and “a longing for home had been stirred in him by the presence of the two women.”

From what he overheard, Samuel related to Hannah and Mary that when they reached St. Francis, they would be stripped of their clothes and forced to “run the gauntlet”, as apparently was the custom with new captives. Before the band of Indians and captives set out on the next leg of their journey, it was apparently here that Hannah saw her only chance to escape. She observed that, while on the island. her captors had let down their guard and had grown careless. In Hannah’s words later, she reasoned that the Indians believed that the two women were too weak to attempt an escape, especially on an island with the river in flood. Guards were no longer posted at night. Hannah determined that, with Samuel and Mary, she might overwhelm the small band of Indians, particularly if there was added the element of surprise. She related later that she persuaded Samuel to ask Bampico, the only Indian of the party whose name is known, how he killed the English quickly. Bampico pointed to the temple of his head and stated how to strike quickly and kill the victim.

Hannah’s plan was simple, she related later. At night, when the Indians were asleep, she and Mary and Samuel, having hidden some hatchets earlier, would position themselves at the heads of two of the Indians. At the signal from Hannah, they would begin the attack. Only one Indian was to be spared, a young boy. Hannah decided to take him back to Haverhill with her if she could make it back to her home.

It was very late on the night of the 30th March 1697. With only the light from two fires and the Moon, Hannah, Mary, and Samuel stood ready to strike. The sound of the rushing river made for a good cover, and then, at Hannah’s signal, the three captives struck their opponents by sharply bringing the blades down into the temples on the sides of their heads. Suddenly, Hannah related later, all was confusion. After the first blows, Mary and Samuel did not continue to dispatch the Indians; it was Hannah who raised her hatchet again and again. When she was done, and all of the Indians were still, Hannah paused, out of breath, covered in blood. Hannah later said that Samuel had killed just one; Mary agreed to kill one of the three Indian women—she was a badly wounded squaw who had managed to survive and escape, and she took the Indian boy Hannah had intended to take back to Haverhill.

“Her slaying of her captors at Contoocook Island March 30, 1697, and escape”

Junius Brutus Stearns: “Hannah Duston Killing the Indians” (1847). Oil on canvas.

Hannah did not scalp the dead right away. She said later that she was terrified that her plan will fail. The wounded squaw was making her way to the other Indian band, only a bit farther upriver. A white captive with the other band later reported that he saw the squaw stagger in, bleeding “from seven wounds of the head and face,” and told the ghastly story of Hannah’s attack.

Hannah gathered up what food was at hand, and told Mary and Samuel to dress in Indian clothes. She took her bloody hatchet and her dead captor’s flintlock rifle and carried all this to the bank of the Merrimack River, where she packed one of the Indians’ canoes and scuttled the others. Hannah related that they were moving away from the island when she suddenly stopped rowing, turned the canoe around, and returned to the island, leaving Samuel and Mary at the edge of the river in the canoe. Thinking about what the Indians did to her six-day-old infant daughter, Martha, Hannah went back to the scene of the bloodbath, took a knife she found among the belongings of the camp and scalped all ten of the Indians, including six children. Then she found the large piece of cloth that had been taken from her loom in Haverhill and wrapped the ten scalps into the cloth. In the river, she washed her hands, the hatchet, and the knife, and got back into the canoe for the journey south; they traveled only at night to avoid detection and capture.

Statue placed on the island at the scene of the attack on the Indians.

Detail of the statue, showing a determined Hannah holding ten Indian scalps

“Her return”

With Mary and Samuel, Hannah reached Haverhill several days later. Her husband and children were overjoyed to find her and Mary alive. Hannah related the story of Martha’s death, and of her journey with the Abenakis, and she displayed the contents of the bloody cloth. A few weeks later, Hannah, Mary, Samuel, and Thomas traveled to Boston, where they petitioned the General Court for money for the scalps. The Colony of Massachusetts Bay had posted a bounty of 50 Pounds per scalp in September 1694, which was reduced to 25 Pounds in June 1695, and then entirely repealed in December 1696. Wives had no legal status in those days, so Thomas petitioned the Legislature on behalf of Hannah Duston, requesting that the bounties for the scalps be paid, even though the law providing for them had been repealed:

“The Humble Petition of Thomas Duston of Haverhill Sheweth That the wife of ye petitioner (with one Mary Neff) hath in her Late captivity among the Barbarous Indians, been disposed of and assisted by heaven to do an extraordinary action, in the just slaughter of so many of the Barbarians, as would by the law of the Province which [only] a few months ago, have entitled the actors unto considerable recompense from the Publick. That tho the [want] of that good Law [warrants] no claims to any such consideration from the publick, yet your petitioner humbly [asserts] that the merit of the action still remains the same; and it seems a matter of universal desire thro the whole Province that it should not pass unrecompensed… Your Petitioner, Thomas Duston.”

On the 16th June 1697, the Massachusetts Bay General Court voted to give them a reward for killing their captors; Hannah Duston received 25 Pounds, and Mary Neff and Samuel Leonardson split another 25 Pounds:

“Vote for allowing fifty Pounds to Thomas Duston in behalf of his wife Hannah, and to Mary Neff, and Samuel Leonardson, captives escaped from the Indians, for their service in slaying their captors. Voted, in concurrence with the representatives, that there be allowed and ordered, out of the public treasury, unto Thomas Duston of Haverhill, on behalf of Hannah his wife, the sum of twenty-five Pounds; to Mary Neff, the sum of twelve Pounds ten Shillings; and to Samuel Leonardson, the sum of twelve Pounds ten Shillings as a reward for their service.”

It was in Boston that Hannah was invited to meet Samuel Sewell, the prominent judge of Massachusetts Bay, and Cotton Mather, a prominent Puritan clergyman, and writer who had been involved in the Salem Witch trials five years before, in 1692. Hannah related to Cotton Mather the entire story of the Haverhill Raid and of her capture, the journey with the Abenakis north, her killing and scalping of the Indians, and the journey back to Haverhill with Mary and Samuel. Mather was a prolific author; he was highly impressed with Hannah, and he related Hannah’s entire story in his Magnalia Christi Americana, which was widely read in all of the American colonies. The governor of the Colony of Maryland later sent Hannah a pewter tankard in honor of her miraculous escape from the Abenakis.

The historic 1700 Duston residence today in Haverill, Mass.

Hannah and Thomas used the scalp money to buy more land on the river, and in 1700, Thomas built the brick house to replace the one the Abenakis burned in the Haverhill Raid. It still stands today and is on the Register of Historic Places.

In the Haverhill Historical Society, one can find, in a glass case, the hatchet, the knife, the bloody loom cloth, and a teapot belonging to Hannah. On the walls behind glass are Hannah’s Confession of Faith, and Cotton Mather’s description of Hannah’s capture, escape, and the killing and scalping of the Indians.

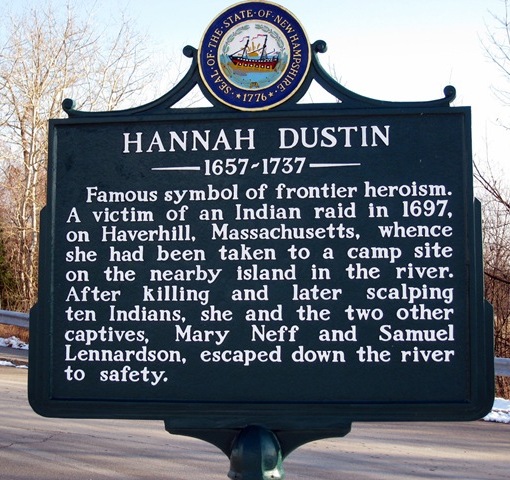

New Hampshire historical marker at the site where Hannah killed & scalped the Abenakis.

Following her return from captivity, Hannah soon gave birth to a daughter, Lydia, in October 1698. Ultimately, Hannah had given birth to thirteen children; three died in infancy including the murdered Martha. Hannah Duston is believed to have died in Haverhill on the 6th of March in 1737 or 1738, at the age of 90.

So closes the tragedy which ended with A Mother’s Revenge.

Local News

Pearl Harbor: The Day That Changed America Forever

An Infamous Day in American History

On December 7, 1941, a day President Franklin Roosevelt declared would “live in infamy,” the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, was attacked by Japanese forces. This catastrophic event not only led to the loss of over 2,300 American lives but also marked a pivotal moment in world history, catapulting the United States into World War II.

A Nation Shaken and Mobilized

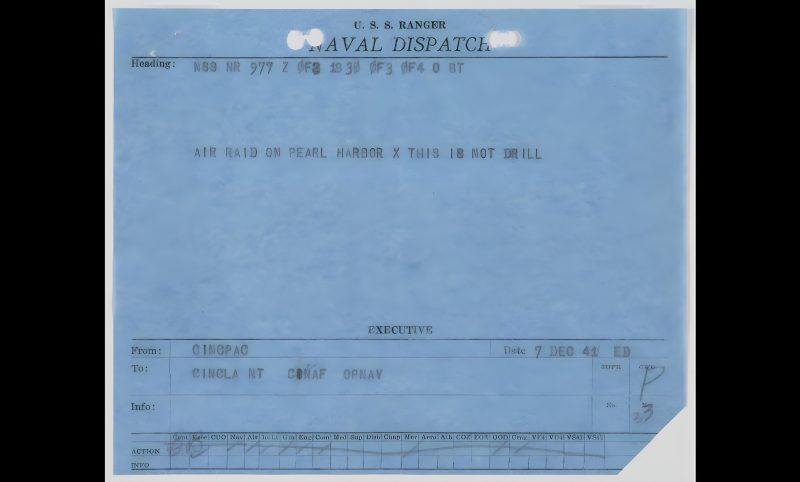

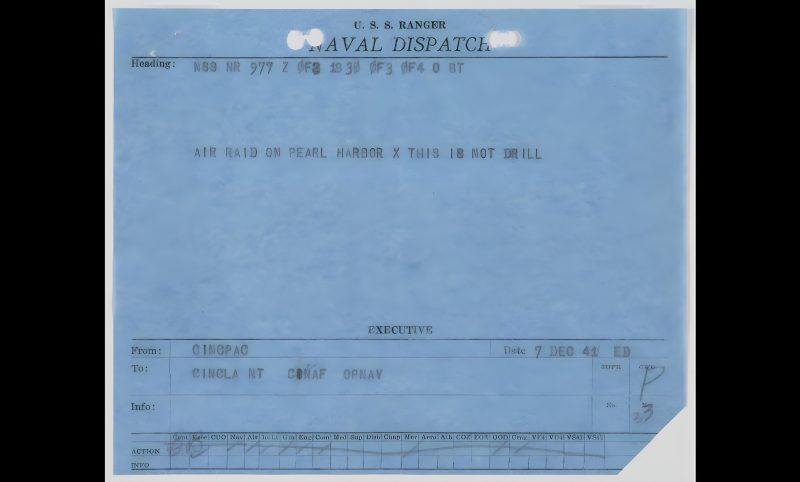

The attack on Pearl Harbor caused unprecedented destruction. The U.S.S. Arizona was obliterated, and the U.S.S. Oklahoma capsized, among other significant losses. Admiral Husband Edward Kimmel’s urgent dispatch encapsulated the shock and severity of the situation: “AIR RAID ON PEARL HARBOR X THIS IS NOT DRILL.” The following day, Congress declared war on Japan, signifying the end of America’s isolationism and the beginning of its significant role in World War II. The nation rapidly transitioned to a wartime economy, accelerating armaments production for military campaigns across multiple fronts.

The Human Response: Voices from the Aftermath

In the wake of the attack, Alan Lomax, head of the Library of Congress Archive of American Folk Song, sought to capture the public’s immediate reactions. Folklorists recorded diverse perspectives, from a Californian woman in Texas lamenting the rise of hatred to ordinary Americans grappling with the sudden thrust into a global conflict. These “man on the street” interviews offer a poignant glimpse into the national psyche at a time of great uncertainty and sorrow.

Propaganda and Patriotism

The Office of War Information (OWI), established months after the attack, utilized collective fear and outrage to bolster support for the war effort. The OWI effectively mobilized public sentiment and labor toward the war cause through propaganda that highlighted American patriotism.

Preserving History: Library of Congress’s Role

The Library of Congress plays a crucial role in preserving the memories of Pearl Harbor. It houses an annotated NBC news report script from December 7, 1941, emphasizing the news delivery’s gravity. The Library’s extensive collection includes recordings of wartime broadcasts, post-battle assessments, and even stories from World War II veterans, offering a comprehensive look into the era’s history.

NBC Program Book. Annotated typescript, December 7, 1941; Microphone, ca. 1938. In World War II, Memory Gallery. American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Motion Picture, Broadcasting & Recorded Sound Division

The attack on Pearl Harbor remains a defining moment in American history. It led to a major shift in global politics and deeply affected the American spirit. The collective memory of this event, preserved through various mediums, continues to remind us of the resilience and unity displayed in the face of adversity.

Local News

9/11: a personal memoir

(Author’s note: this commentary was written on Sept. 11 and 12, 2001, as events transpired. It has since been reprinted in various edits, in various years on the anniversary of those 9/11 terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. Today, September 11, 2022, 21 years on from that horrific day, let us pause and remember, not only those who died and those they left behind, but the specific example of those first responders who walked into danger to offer a helping hand to those trapped inside the twisted wreckage of hatred delivered to NYC, but did not walk out. For it is their example and sacrifice on that day that points humanity toward a better future where 9/11’s and Kabul Airport bombings are a part of our past, rather than the expectation for our collective future.)

September 11, 2001: The faint ring of a telephone stirred me from a restless sleep. I grudgingly opened my eyes and realized that it was fairly early in the morning on Tuesday, a weekend for me in my current employment cycle … I stumbled into my adjacent office and without my glasses tried to make out the caller ID through a sleep-encrusted blur. I lift the receiver.

“Turn on your television!” my friend Dewey’s voice commanded excitedly. “We were watching one of the World Trade Center buildings burning after a plane ran into it about 15 minutes ago and another one just flew into the other building!”

“When?” – Reality and dreams seemed to be mixing though I thought I was awake.

“Now!!! A second ago,” Dewey said & I knew this was not a “Jerky Boys” prank phone call. I hung up the phone without responding. I understood as my mind snapped to, that the information was presented not for discussion, but for action. I was at my complex of three televisions at the far end of my third-floor loft apartment over the Main Street Mill that was so reminiscent to me of the fifth-floor walkup loft I had sublet for a year 11 blocks north of the World Trade Center some 20 years earlier. I hit the “on” button on the smallest of the three, the old 13-inch that I had gotten from my mom. It sat several feet from my living area couch and was my preferred home-alone viewing screen. Perhaps its size helped me maintain the illusion that I wasn’t really addicted to it.

The crystal-sharp satellite picture quickly appeared, I picked up the remote and punched in 970, the satellite channel for the NBC affiliate in Washington, D.C. As a child, it would, as likely as not, have been the morning news station I would be watching as I got ready for school and my parents prepared for their respective federal government jobs in D.C. and Rosslyn, Virginia.

There they were, the twin towers gleaming on a bright September morning against a cloudless, bright, blue sky – except for the huge plumes of black smoke pouring from the top 20 or so floors of both buildings. I flashed on the old ’70s movie “Towering Inferno”. How did that movie I’d never seen more than about 10 minutes of at a time end?!? How many were saved? How long did it take to finally – just burn out?

Bryant Gumble’s calm TV voice hypnotically recited the facts as known at – I flicked the info button to see the time, 9:07 a.m.

“Two planes … believed to be a 737 and a 767 … 18 minutes apart … North Tower first, then the South Tower … Not known if intent or accidents … Here it is. Watch to the right of your screen and you’ll see the second plane as it approaches and plows into the South Tower.”

Oh man, that wasn’t an accident!! There was malevolent intent apparent the first time I saw it. That building was a target. But can’t alarm the public with unsubstantiated theories – public, I have public there!!!

I raced back to my office for the phone. Stuart and Annie Lee, my friends since college days in Richmond, Virginia, at old VCU, the urban university; Stuart and Annie, whom I sublet that Lower Manhattan loft from in 1979-80, when I had my New York state of mind experience, still lived in that five-story walkup, 11 blocks from the World Trade Center.

Two-one-two, two-zero-two, NYC/DC, I always transpose those area codes in my head. I focus and dial two-one-two … The line picks up on the second ring. It is Annie’s voice, “Hello” – she seems breathless.

“Annie, what the hell is going on up there,” I blurt out not letting on how relieved I am to hear her voice.

“I don’t know but it’s pretty bizarre,” she replied.

We used to joke about whether the North Tower, the closest one to their loft, would fall on their building if it tipped over on its side northbound. It seemed that close, those big rectangles looming out of the back loft windows and over the rooftop deck Stuart had built. That was after their 1977 wedding in Charleston, South Carolina, Annie’s home turf. I glanced at the time on the caller ID. It was 9:11 a.m. – REALLY?!? I thought without verbalizing it.

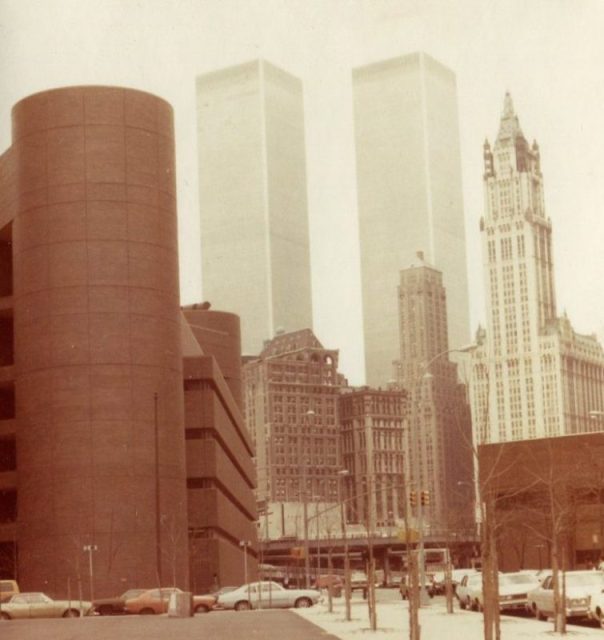

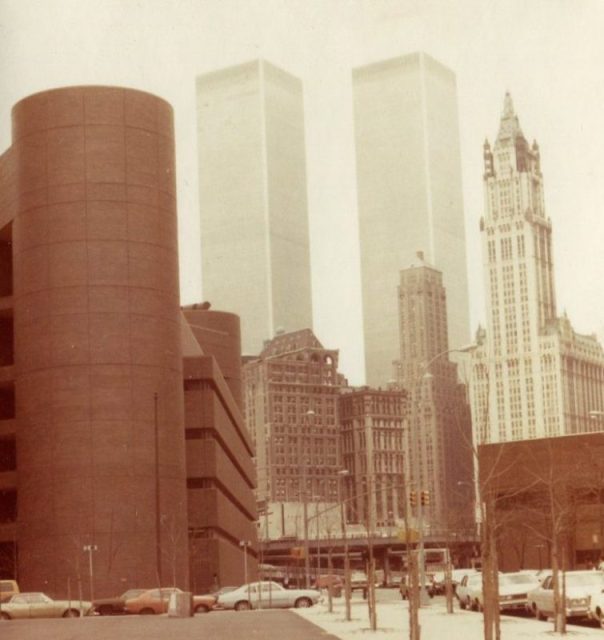

The World Trade Center twin towers presented a surreal backdrop to lower and even near mid-town Manhattan, as pictured here when the author lived 11 blocks north of them in 1980. – Photo/Roger Bianchini

“I just saw a tape of the second plane hitting the second building,” I said.

Annie hesitated, then said, “Roger, I was down there when they exploded.”

I was stunned. She had been closer than her home, at 9 in the morning. Was she nuts? What was Annie, an artist, a sculptor doing in the financial district at 8:45 in the morning? I must have verbalized the question as well as thought it.

“I was at the fish market they have in the parking lot on the east side of the Trade Center on Tuesdays and Thursdays (that’s an acceptable reason, I thought). We heard a plane and we all ducked. We knew it didn’t belong there so low over the city. Then the building exploded and we had to run under this building overhang to get away from all the burning debris that was coming down after the explosion. After the second explosion I thought I better get out of there and I went to look for my bike, which was on the Trade Center side. Luckily it was OK and I just came in the door when you called.

“You said the plane HIT the building?” she trailed off, apparently just making the connection between the low-flying plane that had caused those at the fish market to duck reflexively and the first explosion. “I didn’t, we didn’t – Listen Roger, I don’t mean to cut you off but I want to clear the line for my mom. I know she’s going to try and call or I should call her before the lines get clogged up.”

“OK, sure. Where’s Stuart,” I wanted to make sure the calm in her voice included knowledge of Stuart’s whereabouts before we disconnected.

“He’s here.”

“Good. You all take care and stay in touch.” I hung up.

They were OK.

That she was down there in physical jeopardy had jolted me …

I was back at the TV. I plopped on the couch. It was 9:15. It was like I was hypnotized, the emotional trauma of world-changing events perceived at an almost subconscious level. In a weird way it was like 1963 and 1968. But no, it was 2001 – the real first year of not only a new century but a new millennium; 2001, much bigger deal than 1901; none like it since 1001 – a thousand-year bookmark on the pages of history. So, I channel surf throughout the morning of September 11, 2001.

The World Trade Center, the Pentagon are in flames!! All air traffic to the U.S. being diverted and all planes in the states being brought down. – How?

“A plane down in the woods of western Pennsylvania – Camp David may have been the target” is theorized on the air.

BUT THEN – a huge plume of smoke in lower Manhattan. What the …?!?!

Is there only one building there?

It’s gone.

In a panic I look for competent reporting and a familiar voice. CNBC broadcasts from lower Manhattan, competent, who knows; familiar and boots on the ground, yes.

“One of the two World Trade Center towers has collapsed,” a camera shot from across the Hudson River – lower Manhattan looks like it is on fire – back to NWI (News World International) – they had the live feed from a New York City ABC affiliate earlier with a poor guy on the phone who was trapped on the 85th floor because the fire doors had locked up – which building was he in? Is he dead? He said things were under control and stabilizing and he was giving directions to where he and one other person were trapped with windows blown out – the firemen must have been going up …

Watching NWI with their main Canadian affiliate as … the … second tower … collapses from the top down – “Oh my God. Oh my God” the on-air voice repeats calm but distraught – how is that even possible? – as off camera, yelling and screaming with no pretense of calm maintained as the North Tower joins its sibling on the ground … where am I?!!? Two 110-story buildings … gone …

I watch lower Manhattan from across the Hudson River again. It is totally enshrouded in smoke. Are people suffocating in that? Could you breathe in there?

Again try Stuart and Annie. Nothing …

Then tears came and I sobbed with worry for my friends and for my old neighborhood; for 50,000 or 5,000 people, I didn’t know; for two buildings that had stood like a magical, surrealistic backdrop to an already magical skyline for a quarter of a century or more; for the firemen and the cops who went in there trying to get trapped people out … It’s just enormously, monumentally tragic and screwed up and I don’t feel bad about crying …

That it has come to this is tragic in more than the obvious ways. – Things will never be the same. A dark thought flashes into my consciousness – is that what it is really all about?

As the day progresses I follow the pending collapse of adjacent buildings, watch ghost-like, dust-covered people stumble, walk calmly with their briefcases or run from the rubble and spreading, spewing cloud that covers lower Manhattan.

As the skies over America clear of all air traffic for the first time in the age of air travel, an age that has existed all of my life, I wonder how the next attack will come, who will bring it and why …

As the day progressed into night, lower Manhattan took on an eerie look as powerful spotlights bracketed debris and the continually rising cloud of smoke from fires burning deep within the rubble of 220 stories, estimated at 1.2 million tons of debris that will take a year to clear …

Who knows how long it will take my mind – or anyone’s – to assimilate what has happened.

By Roger Bianchini

Sept. 11-12, 2001

Looking Back

Ben Franklin and his miraculous lightning rod

What would you think if you saw a man on horseback chasing a thunder and lightning storm? You might probably wonder what on Earth he was trying to do. Well, if you lived in the mid-1700s and knew Benjamin Franklin, this is just what you might see during a terrible storm. Ben was fascinated by thunderstorms; he loved to study them. If he were alive today, we could probably add a “storm-chaser” to his long list of titles and achievements.

In a dialogue held in Philadelphia on a very warm morning at the end of June 1776, when Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress John Adams had a conversation with Pennsylvania delegate Dr. Benjamin Franklin about the writing of the Declaration of Independence by Virginia delegate Thomas Jefferson; they were discussing the importance of the document and who might be remembered for their part in bringing it to reality :

John Adams: “It doesn’t matter, Franklin. I won’t be in the history books anyway, only you. Franklin did this and Franklin did that and Franklin did some other damn thing. Franklin smote the ground and out sprang George Washington, fully grown and on his horse. Franklin then electrified him with his miraculous lightning rod and the three of them – Franklin, Washington, and the horse – conducted the entire revolution by themselves.”

Ben Franklin is known for his experiments with electricity (most notably the kite experiment in June 1752, described in the previous edition of LOOKING BACK), a fascination that began in earnest after he accidentally shocked himself six years earlier, in 1746. By 1749, he had turned his attention to the possibility of protecting buildings—and the people inside—from lightning strikes. Having noticed that a sharp iron needle conducted electricity away from a charged metal sphere, he theorized that such a design could be useful:

“May not the knowledge of this power of points be of use to mankind, in preserving houses, churches, ships, etc., from the stroke of lightning, by directing us to fix, on the highest parts of those edifices, upright rods of iron made sharp as a needle…Would not these pointed rods probably draw the electrical fire silently out of a cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible mischief!”

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: “I like it.”

In other words, lightning rods would draw the static electricity from the air during a thunderstorm, and conduct it safely to the ground, thus eliminating the accumulation of electrical charges which results in a discharge of lightning.

Franklin’s pointed lightning rod design proved very effective and soon topped buildings throughout the Thirteen Colonies.

It was in Boston, Massachusetts, in the year 1746 when Franklin first stumbled upon other scientists’ electrical experiments. He quickly turned his home into a little laboratory, much to wife Deborah’s chagrin, using machines made out of items he found around the house. During one experiment, Ben accidentally shocked himself. In one of his letters, he described the shock as “…a universal blow throughout my whole body from head to foot, which seemed within as well as without; after which the first thing I took notice of was a violent quick shaking of my body…” (He also had a feeling of numbness in his arms and the back of his neck which gradually wore off.)

Franklin spent the summer of 1747 conducting a series of groundbreaking experiments with electricity. He wrote down all of his results and ideas for future experiments in letters to Peter Collinson, a fellow scientist and friend in London who was interested in publishing Ben’s work.

Franklin’s original pointed lightning rod, after being struck by lightning during his experiments. Courtesy The Franklin Institute, Philadelphia.

By July of 1747, Ben used the terms positive and negative (plus and minus, or + and -) to describe the positive and negative electrical charges, instead of the previously used words “vitreous” and “resinous” used in describing liquids; lightning at the time was universally believed to have been a fluid—electric fluid. Franklin described the concept of an electrical storage battery in a letter to Collinson in the spring of 1749, but he wasn’t sure how it could be useful. Later the same year, he explained what he believed were similarities between electricity and lightning, such as the color of the light, its crooked direction, crackling noise, a distinct smell now known to be ozone, and other things. There were other scientists who believed that lightning was electricity, but Franklin was determined to find a method of proving it.

By 1750, in addition to wanting to prove that lightning was electricity, Franklin began to think about protecting people, buildings, and other structures from lightning. This grew into his idea for the lightning rod. Franklin described an iron rod about 8 or 10 feet long that was sharpened to a point at the end.

Ben wrote, “the electrical fire would, I think, be drawn out of a cloud silently before it could come near enough to strike…”

Two years later, Franklin decided to try his own lightning kite experiment. Surprisingly, he never wrote letters about the legendary kite experiment, and only one article which appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette in October 1752; the British scientist Joseph Priestly wrote the only other account fifteen years after it took place.

To recap from the previous LOOKING BACK column: in June of 1752, Franklin was living in Philadelphia and waiting for the steeple on top of Christ Church to be completed so he could conduct his lightning experiment (the steeple would act as the “lightning rod”). He grew impatient and decided that a kite would be able to get close to the storm clouds just as well. Ben needed to determine what he would use to attract an electrical charge; he decided on a metal house key and attached it to the kite. Then he tied the kite string to an insulating silk ribbon for the knuckles of his hand. Even though this was a very dangerous experiment, (you can see what the lightning rod in the photograph looks like after being struck), some people believe that Ben wasn’t injured because he didn’t conduct his test during the worst part of the storm. At the first sign of the key receiving an electrical charge from the air, Franklin knew that lightning was a form of electricity and not a fluid. His son William was the only witness to the event.

The very first photograph of lightning, by William N. Jennings. Courtesy George Eastman Museum, Rochester, N.Y.

Two years before the kite and key experiment, in 1750, Ben had observed that a sharp iron needle would conduct electricity away from a charged metal sphere. He first theorized that a lightning strike might be preventable by using an elevated iron rod connected to earth to empty static electricity from a cloud. Franklin articulated these thoughts as he pondered the usefulness of a lightning rod:

“May not the knowledge of this power of points be of use to mankind, in preserving houses, churches, ships, etc., from the stroke of lightning, by directing us to fix, on the highest parts of those edifices, upright rods of iron made sharp as a needle…Would not these pointed rods probably draw the electrical fire silently out of a cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible mischief !”

Franklin began to advocate lightning rods with sharp points. Conversely, his English colleagues favored blunt-tipped lightning rods, reasoning that sharp ones attracted lightning and increased the risk of strikes; they thought blunt rods were less likely to be struck. King George III had his palace equipped with blunt lightning rods. When it came time to protect the buildings in the English American colonies’ buildings with lightning rods, the decision became a political statement. The pointed lightning rod expressed support for Franklin’s theories of protecting public buildings and the rejection of theories of blunt iron rods supported by the King. The English thought this was just another example of the flourishing American colonies being disobedient to the British crown.

Franklin’s lightning rods could soon be found protecting many buildings and homes. This BRI journalist’s note: My two-story home near Amissville, constructed in 1999, is built upon the highest point of my property, and with a metal roof, the contractor thought it wise to have lightning rods installed. There are four of them, with dark green glass globes, placed on the ridge of the pitched roof, and a fifth pointed rod mounted on the chimney.

All of the pointed lightning rods are connected to a large-diameter stranded copper wire which is attached to a copper grounding rod buried deep in the ground in the front of my house. Knock on wood, in the past twenty years, my home has not been struck by lightning.

The lightning rod constructed on the dome of the State House in Maryland was the largest “Franklin” lightning rod ever attached to a public or private building in Ben’s lifetime.

It was built in accord with Ben’s recommendations, and in the more than two hundred plus years ever since, has had only one recorded instance of a lightning strike:

Three years ago today, July 1st, 2016: Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan said the Maryland State House in Annapolis was saved from a lightning strike “by a 208-year-old original Ben Franklin lightning rod.”

Ben Franklin’s original design for structural lightning protection.

Courtesy The Franklin Institute, Philadelphia.

The nation’s oldest State House was hit by lightning Friday evening [July 1st], triggering a sprinkler system in its historic dome. Fire officials said there was no smoke or fire in the building, no damages, and no one was injured.

The governor said that the lightning rod on the dome “was constructed and grounded to Franklin’s exact specifications.” He said at the time it was added to the building, it served as “a powerful symbol of the independence and ingenuity of our young nation.”

The pointed lightning rod placed on the Maryland State House and other buildings also is a symbol of the intellect and the inventiveness of Dr. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of our country, and the inventor of the miraculous lightning rod.

Looking Back

The Year Without A Summer : “Eighteen Hundred & Froze To Death”

The year 1816 was known as “ The Year Without a Summer” in New England because six inches of snow fell in June, and every month of that year had a hard frost.

Temperatures dropped to as low as 40 degrees F. in July and August as far south as Connecticut. People also called it “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death” and the “Poverty Year.”

The Year Without A Summer had a far-reaching impact. Crop failures caused hoarding and big price increases for agricultural commodities. People went hungry. Farmers gave up trying to make a living in New England and started heading west. Politicians who ignored the melancholy plight of their constituents found themselves voted out of office.

Most scientists agree that what most likely caused the bizarre weather in The Year Without a Summer was the monumental explosive eruption of the volcano Mt. Tambora in Indonesia in April 1815, the year before. Said to be the loudest explosion in recorded history—even slightly surpassing that of Krakatoa in August 1883— the volcano put out such a volume of dust, ash, and chemical cloud high into the atmosphere that it lowered worldwide temperatures by half a degree; while that may not seem much, the global cooling was responsible in the U.S., for frosts and cold weather which ravaged the New England growing season, prompting cries of a “year without a summer”, and migration into western territories and states. Plunging temperatures also broke the monsoon cycle in Asia, sending India into famine and triggering a cholera epidemic of unprecedented severity.

The dust and ash clouds in the high atmosphere also produced some of the most spectacular sunsets ever witnessed, with most of them of green or violet hues. There were warm days in the spring of 1816, but they were followed by cold snaps. In Salem, Mass., for example, it was 74 degrees F. on the 24th of April. Within 30 hours the temperature dropped to 21 degrees F.

Thomas Robbins, the East Windsor, Conn., bibliophile, noticed the late spring of 1816. He wrote in his diary, “the vegetation does not seem to advance at all.”

On the 12th of May, strong winds and freezing temperatures from Canada killed the buds on fruit trees. Inch-thick ice formed on ponds and streams from Maine to upstate New York. By the end of May, corn plants froze in central Maine.

Then, on the 6th of June 1816, six inches of snow fell on New England. Clockmaker Chauncey Jerome of Plymouth, Conn., wrote in his autobiography that he walked to work that day wearing heavy woolen clothes, an overcoat, and mittens.

Chauncey Jerome

Snow flurries fell in Boston the next day, the latest ever recorded. The snow was 18 inches deep in Cabot, Vt., on the 8th of June. Three days later, on the 11th of June, a temperature of 30.5 degrees F. was recorded in Williamstown, Mass. Frozen birds dropped dead in the fields; in Vermont, some farmers who had already shorn their sheep tried to tie their fleeces back on, but many froze to death anyway.

Benjamin Harwood, a Bennington, Vt., farmer, wrote in his diary for the 11th of June that “…it rained all night, then it began to snow from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. The tops of all the mountains on every side were crowned with snow. The most gloomy and extraordinary weather ever seen.”

And then it got warm again.

Temperatures seesawed up and down throughout the Year Without a Summer, bringing hope on warm days that the crops could be harvested after all. Then sharp cold spells brought new despair. On the 22nd of June, for example, temperatures reached 101 degrees F. in Salem, Mass. But the 4th of July was quite cool. Our Plymouth, Conn., clockmaker observer Chauncey Jerome noted in his autobiography that it was hard to feel patriotic while watching men play quoits in overcoats. Then a northwest wind brought a three-day cold spell, with 30-degree cold temperatures in northern New England, and 40 degrees F. in Hartford and New Haven.

The frost destroyed the bean crop in Franconia, N.H., and bean, cucumber, and squash crops in Kennebunkport, Maine. Young plants grew so slowly they were vulnerable to frost, and farmers harvested so little hay they had to either slaughter their livestock or feed them oats and corn. As depressing as the second severe cold spell was, the drought which enveloped most of the United States, including New England, seemed worse. “I never saw our streets so dry,” complained a minister in East Windsor, Conn.

Gov. William Jones of Rhode Island issued a proclamation designating a day of public ‘Prayer, Praise and Thanksgiving,’ noting the “coldness and dryness of the seasons” and the “alarming sickness.” In New Hampshire, Gov. William Plumer believed the weather was divine Providence’s judgment in the earth and urged people to humble themselves for their transgressions. Fears of famine began to grow during the Year Without a Summer.

William Plumer

He blamed God for the Year Without a Summer.

Early August was sunny and warm. Farmers planted new crops, hoping the growing season might last beyond the first frost in October. But on the 13th and 14th of August, a cold spell froze the corn crop on farms north of Concord, N.H.

Less than a week later, on the 20th of August, at Amherst, N. H., a short but violent storm struck, signaling a steep drop in temperature of 30 degrees within a few hours. It snowed that day in Vermont; in Maine, farmers wrapped rags around their plants to protect them.

In some of the New England states, at least the wheat, rye, and potatoes were holding up, staving off famine. In Ashland, N.H., Reuben Whitten was able to grow wheat on his south-facing farm. He shared what he had with his neighbors. After he died thirty years later, in 1847, his neighbors paid for his gravestone and later erected a monument that read, in the spelling of the local stonecutter :

“A pioneer of this town. Cold season of 1816 raised 40 bushils of wheat on this land whitch kept his family and his neighbours from starveation.”

Hopes of salvaging what remained of the corn crop were dashed by another severe frost on the 28th of August. In Maine and New Hampshire, farmers cut-up whole fields of corn for cattle and horse fodder. Writing in his diary in Kittery, Maine, Rev. William Fogg summed up the Year Without a Summer: “Crops cut short and a heavy load of taxes.”

There were reports of people eating raccoons, mackerel, and pigeons.

As is usual in early Autumn in New England, the days warmed up again in September, but then at sunrise on the 26th of September in Hanover, N.H., thermometers read 26 degrees F. Snow fell throughout the region, followed by a killing frost which froze crops in the field and apples on the branch. As if this was not enough, the drought caused wildfires to break out in the woods throughout New England. Fires in western New York produced so much smoke that sailors were blinded on Lake Champlain.

The Year Without a Summer was especially hard on the poor. The New Hampshire Patriot reported on the 22nd of October 1816: “Indian corn, on which a large proportion of the poor depends, is cut off.” Vermont farmers lost much of their livestock, and Vermonters foraged for food such as nettles, wild turnips, and hedgehogs.

Three-quarters of the corn crop throughout New England was lost during Eighteen Hundred & Froze To Death. Prices soared for wheat, grains, meat, vegetables, butter, milk, and flour. In Maine, the price of oats tripled and potatoes doubled. Hay was $180 a ton in parts of New Hampshire—six times its usual cost.

New England was not the only region afflicted by global cooling. 1816 brought cold and widespread famines in Europe as well. The bad weather in Switzerland forced a group of poets of a literary club to remain in their rooms. In a friendly competition among the writers, the group held a contest to see who could write the best piece. Perhaps reflecting on the atmospheric conditions and the boredom they brought, Mary Shelley wrote her tale of Frankenstein.

At least the Year Without a Summer had been good for producing maple syrup in Vermont, and Vermonters traded syrup for fish, which is why they called 1816 the “Mackerel Year.”

In Washington, Members of Congress seemed insensitive to the suffering of the people they were elected to represent and voted to double their own salaries. It did not go over well. Nearly 70 percent of the incumbent U.S. representatives were voted out of office in the next elections. Daniel Webster of Massachusetts was one of them.

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster lost his bid for re-election during the Year Without a Summer.

In 1817, after the Year Without a Summer was history, Josiah Meigs, commissioner-general of the Land Offices, began a more systematic approach to observing weather phenomena. He ordered the twenty Land Offices under his authority to take thrice-daily recordings of the temperature, winds, and precipitation. Author Samuel Goodrich visited New Hampshire, observing:

Samuel Goodrich

Samuel Goodrich described the despair that seized people during the Year Without a Summer.

“At last a kind of despair seized upon the people. In the pressure of adversity, many persons lost their judgment, and thousands feared or felt that New England was destined, henceforth, to become part of the frigid zone.” Indeed, 1817 started out cold as well, convincing Northeast farmers it was time to migrate to the Midwest.

Rev. Samuel Robbins in East Windsor, Conn., wrote, “We have had a great deal of movings this spring. Our number rather diminished here.”

At the time, many reasons were given for the weird weather phenomena: sunspots, deforestations, great fields of ice floating in the Atlantic, Benjamin Franklin’s lightning rod experiments (more than fifty years before), and, of course, the wrath of God.

As we now know, the Year Without a Summer was most likely caused by the massive volcanic explosion on Mt. Tambora in April 1815, killing 15,000 instantly, and, as time went on, another 65,000 perishing of disease and starvation.