Opinion

HBO’s ‘Chernobyl’ – a stark reminder that the truth awaits us all

Above, Reactor 4 at Chernobyl after its nuclear-tinged ‘roof fire’ was extinguished; below Stellan Skarsgard as Communist Party official Boris Shsherbina uses a reactor model to set the stage for unexpectedly frank trial testimony from nuclear physicist Valery Legasov. Photos Courtesy Liam Daniel/HBO from an HBO/Sky co-production

I’m passing this off as a cinematic TV review but it is really something deeper – as befits HBO’s brilliant five-part mini-series about the April 1986 nuclear reactor explosion at the Soviet Union’s Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, and its aftermath. It is as the concluding summary indicates, an aftermath we likely will never know the full extent of.

But of what we do know, or at least make educated guesses at, in the wake of the world’s worst nuclear power plant disaster:

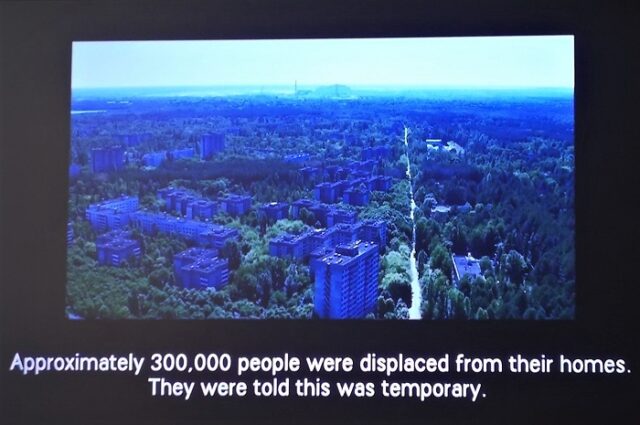

- a 2600 square kilometer portion of former Soviet Republics Ukraine and Belarus now known as The Exclusion Zone;

- it is a zone from which 300,000 people were displaced from their homes and which no one is allowed to return to, to this day;

- it is a zone in which 600,000 people, military and civilian, were conscripted to serve in various tasks from containment, evacuation of the human population to the systematic slaughter, actually mercy killings if you look at the alternative of eventual death from radiation poisoning, of contaminated pets, farm animals and wildlife left behind in The Exclusion Zone;

A view from the town toward the plant at upper center of photo

- it is an accident site where local firefighters were deployed to what was reported as a “roof fire” but had actually been a nuclear explosion at the core of Chernobyl’s Reactor 4. It was a first response most, if not all, would not survive as is emotionally portrayed in the series;

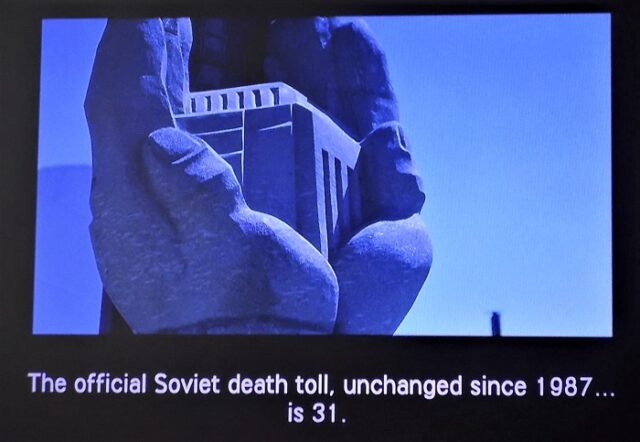

- of the human toll of “Chernobyl” – in the absence of reliable governmental statistics estimates of the direct death toll range wildly from 4,000 to 93,000, with the official Soviet/Russian total unaltered since 1987 standing at a solid 31 deaths attributable to the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

And it is this discrepancy between harsh reality and state-produced fiction that lies at the heart of the HBO/Sky co-production of “Chernobyl”.

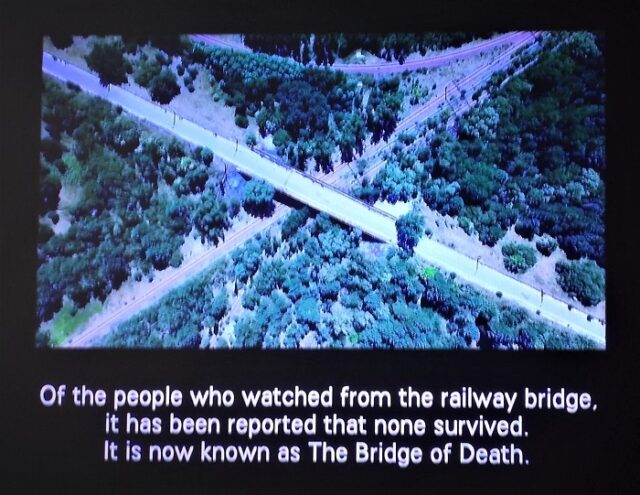

An aerial view of the bridge over railroad tracks at which Chernobyl citizens gathered to watch the flames at the nuclear power plant in their backyard

The opening and closing sequences of “Chernobyl” are the words of the Soviet nuclear scientist assigned to the State-sponsored investigation of the nuclear accident. They are real words from the smuggled-out audio memoir of a real person – Valery (Val-ER-y) Legasov – reflecting on his experience of Chernobyl at its core (nuclear pun intended). And that “core” is the potentially explosive collision between truth and lies at the heart of governmental bureaucracy. Such a collision can result in the same magnitude of explosive force in the socio-political world in which that collision occurs, as that encountered in the atomic and sub-atomic world of nuclear physics.

In a summary of Chernobyl’s aftermath at the series’ conclusion – from which photos of the actual players and involved sites accompanying this review were taken – Mikhail Gorbachev who as Premier of the Soviet Union was one of those players, is quoted in 2006 as observing, “The nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl … was perhaps the true cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Soviet Premier at the time of Chernobyl in 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev had a dire assessment of the ultimate impact of ‘Chernobyl’ on the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev, from his perch at the top of the Soviet governmental apparatus, was in a better position than most, if not all, to make an accurate assessment about the political collapse of one of the two dominant military, political and economic world states to emerge from the ashes of World War II.

For it was former military allies the United States and Soviet Union who launched the world into the second half of the 20th Century: into the nuclear age; into a so-called “Cold War” between disparate economic and political ideologies that dominated the next 40-plus post World War II years. And it had to be a “Cold War” because if it turned hot in this new nuclear age the survival, of not only the loser of that war, but of the winner, the planet and all life on it would be in question.

And it was Chernobyl that happened in that 41st post-World War II year – April 26, 1986. And just over five years later, before the end of December 1991, the Soviet Union no longer existed. And it was not defeat by conquest, but rather by capitulation.

To what?

Perhaps to that TRUTH Valery Legasov worries over at the outset of “Chernobyl” and which he warns at its end, lies in wait for us “for all time”.

For what “Chernobyl” so startlingly portrays is that what exploded on April 26, 1986 was, not only a nuclear reactor in the Soviet Union’s eastern European province of Ukraine, but perhaps even MORE tellingly, the LIES upon which the Soviet Union’s Empire of Cards was built.

As episode one begins in darkness with shuffling sounds we first meet Valery Legasov through his voice alone:

The real Soviet nuclear scientist Valery Legasov, pictured above, knew that one way or another, his work in Chernobyl’s aftermath would be a death sentence for him.

“What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognize the truth at all. What can we do then? What else is left but to abandon even the hope of truth and content ourselves instead with stories? In these stories it doesn’t matter who the heroes are. All we want to know is who is to blame?”

Legasov then informs us that in this story that blame will primarily be placed on Chernobyl’s chief operations officer Anatoly Dyatlov. It was Dyatlov who oversaw the April 26, 1986 systems test designed to power down Chernobyl’s nuclear reactor to facilitate a transfer to traditional diesel back-up systems to allow a one-minute, transitional power gap to be filled in a nuclear reactor emergency situation.

“He was the best choice – an arrogant, unpleasant man. He ran the room that night; he gave the orders; and no friends, or at least not important ones. Now Dyatlov will spend the next 10 years in a prison labor camp. Of course that sentence is doubly unfair. There were far greater criminals than him at work. As to what Dyatlov did do, he doesn’t deserve prison, he deserves death.”

Legasov’s harsh assessment of a man he says is being scapegoated comes as a shock. But the shock is minimized as one begins to comprehend the dire consequences of reckless, careless arrogance in the nuclear context in which Dyatlov existed.

There is a great line from the leader of my favorite group in “Chernobyl” – Soviet coal-miners recruited to dig beneath the destroyed Chernobyl reactor to help build a containment base to prevent a nuclear meltdown from reaching the groundwater supply that would have multiplied the nuclear catastrophe exponentially.

After completing a shift in their coal mine – and it is noted that Soviet coal-miners did have a certain position of power in the Soviet Union due to the nation’s reliance on coal power – the miners are relaxing in a canteen on site. Covered in coal dust, having some shift drinks the mine foreman asks as best I remember, “What is as big as a house; uses enough power to light a city and cuts donuts into four pieces?”

His answer drawing a gale of laughter is, “A Soviet machine designed to cut donuts into three pieces.”

Soviet coal-miners leave their mark on the Minister of Coal who has come to inform them they have been conscripted for emergency work at Chernobyl

The hard truth that may have brought the Soviet Union down was that perpetuating the lies upon which the State was built, was the true priority of the Soviet State – not presenting the world with a Utopian alternative to predatory, mercantile capitalism; not the creation of a workers’ paradise on earth; and not even the provision of safe nuclear power to its population.

It was a lie that went so deep into the fabric of the Soviet system that those conducting a thrice-failed test of backup systems at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant on April 26, 1986, had no idea that their final emergency shut down option for a backup power test gone wrong, a test moving toward a nuclear explosion and meltdown, was the lit fuse that would cause that explosion and meltdown to occur.

“Why” during “Chernobyl’s” climatic trial scene, it is asked would the power plant’s nuclear core cooling rods be graphite-tipped so as to cause a spike in power, rather than the desired immediate shutdown to counter an unplanned power surge?

“For the same reason” a litany of other things in the Soviet Union are done, Legasov, tells the court in what may be a suicidal burst of candor – “Because it is cheaper.”

“Chernobyl” reminds us all, that whichever type of society we live in, under whatever type of political apparatus, that when we allow ourselves to be routinely lied to for political advantage; and we accept those lies without question due to intellectual expediency or laziness, eventually a hard truth may be waiting around an unexpected turn that will remind us that one thing is immune to all the lies – and that is the TRUTH itself.

Jared Harris as Legasov and the real Valery Legasov cross paths over the decades as they fly to Chernobyl to investigate what happened. The ‘gift of Chernobyl’ Legasov said, was a shift in perspectives from a fear of the cost of truth to a fear of the consequences of lies. He was allowed to tell a Soviet show trial the truth of Chernobyl due to such a change in perspective by Communist Party official Boris Shcherbina, under whom Legasov worked on the Chernobyl investigation.

At “Chernobyl’s” dramatic conclusion the words of Legasov, the nuclear scientist isolated into non-personhood by the Soviet state in reaction to his court testimony, voices over the Ukrainian landscape:

“To be a scientist is to be naïve. We are so focused on our search for truth we fail to consider how few actually want us to find it. But it is always there, whether we see it or not, whether we chose to or not. The truth doesn’t care about our needs or wants; it doesn’t care about our governments, our ideologies, our religions. It will lie in wait for all time. And this at last is the gift of Chernobyl. Where I once would fear the cost of truth, now I only ask: what is the cost of lies?”

“Chernobyl” is a welcome reminder of what true cinematic art is: for while life is short, art that plunges into its depths for an explanation, is eternal.

Ukrainian firemen responded to report of a ‘roof fire’ at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in their backyard. Here, Adam Nagaitis as one of those firemen realizes it may not be a typical ‘roof fire’ he has responded to.

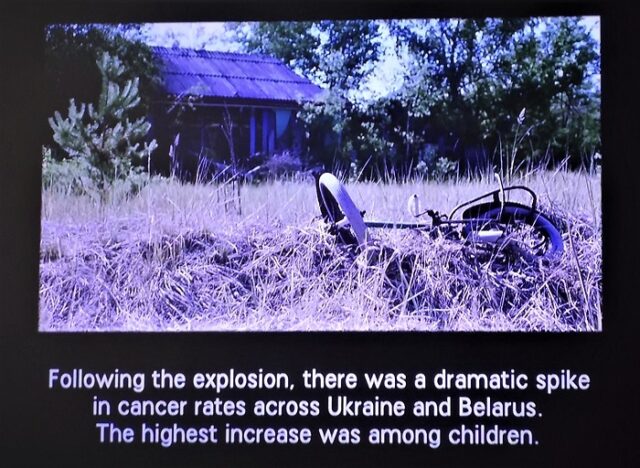

The consequence of years of State lies was harsh in Chernobyl’s aftermath …

And will remain a harsh and threatening specter beyond all our lives …

As at least one initial and persistent lie remains …