Local News

“It Changes Everything”: Citizens Warn of Data Center Impacts in Rural Virginia

What started as a community conversation quickly turned into a passionate call to action.

On Saturday afternoon, May 10th, Warren County residents met at the Warren County Community Center to hear firsthand how data centers—the massive, windowless facilities that power cloud computing and artificial intelligence—are reshaping rural Virginia. For many in the room, it was the first time they had heard the full scope of the issue.

Their host was local resident Aiden Miller, who’s lived in Front Royal for a decade. “This event came out of the growing buzz around data centers — not just in Warren County, but all across Virginia,” Miller said. “I wanted to get everyone in the room to talk openly about what’s really happening.”

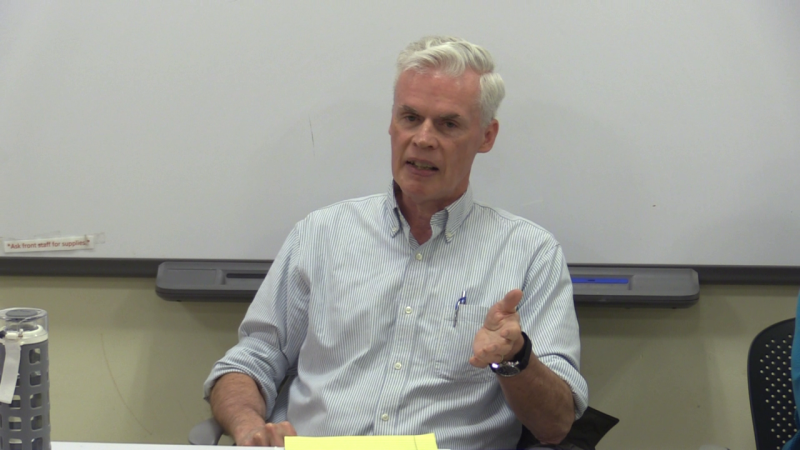

To guide the discussion, Miller invited people with firsthand experience: Warrenton Town Councilman Eric Gagnon, Protect Fauquier co-founder Cynthia Burbank, and later in the evening, Prince William County Supervisor Bob Weir. Together, they painted a detailed and often sobering portrait of what data center development means for small towns — and what it costs.

What Is a Data Center?

“Think of a massive warehouse,” said Burbank. “No windows. It can be a million square feet and sit on 100 acres. Inside are thousands of computers running nonstop. These machines use enormous amounts of electricity and often a lot of water to stay cool.”

“They’re not pretty,” added Gagnon. “And once you have one, more will follow. The infrastructure invites expansion — and so do the profits.”

Data centers have become essential infrastructure for everything from video streaming and social media to AI and federal agencies. But as Loudoun and Prince William counties run out of land, developers are moving west — and Warren County is now in their sights.

Water, Electricity, and Environmental Risks

Water use quickly became one of the meeting’s central concerns, especially in a county where wells and aquifers are the main sources of drinking water.

“These facilities often use water-cooling systems,” Burbank said. “They claim they recycle water, but only to a point. A lot of it evaporates, and they need more. That’s a real threat to aquifers and wells.”

Councilman Gagnon pointed to newer technologies that use glycol — a chemical similar to antifreeze — instead of water. “That sounds high-tech,” he said, “until you ask what happens if 30,000 gallons of glycol leaks into the aquifer. That’s a real risk, and no one’s talking about it.”

“Think of a massive warehouse — no windows, a million square feet, stretching across 100 acres,” said Cynthia Burbank. “That’s what a data center looks like. It doesn’t belong in a small town.”

Electricity demands are just as serious.

“The Digital Gateway project in Prince William is projected to use 3 gigawatts,” said Burbank. “That’s the equivalent of two full-size nuclear power plants.”

In July 2023, Dominion Energy estimated it would need 21 gigawatts to power data centers across Virginia. By December, just five months later, that number jumped to 40 gigawatts.

“And when the grid can’t keep up?” she asked. “They’ll turn on diesel backup generators. Some sites have 100 of them. If you live nearby, you’ll hear them. And breathe them.”

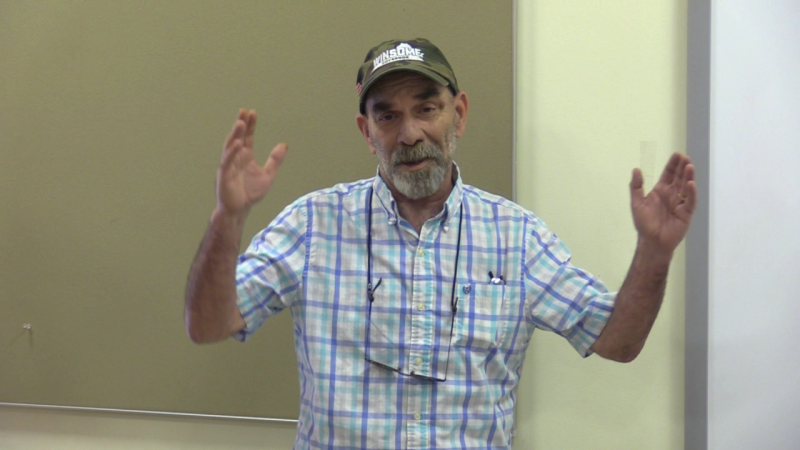

Supervisor Weir, who’s spent over a decade fighting unchecked development, said the risk is immediate. “July 1, you’re going to see your electricity bills go up,” he warned. “And again next July. Dominion passes those costs to you. Not Amazon. Not Meta. You.”

Money Promised vs. Money Delivered

Data center developers often promise a flood of tax revenue for local governments. But the speakers urged residents to look beyond the headlines.

“Yes, they can bring in tax revenue,” Burbank said. “But only if the equipment inside the building is taxable — and that depends on who owns it and what kind of work it’s doing.”

In Manassas, a data center was reclassified as a bank processing facility. Under Virginia law, banks are exempt from certain equipment taxes. “The city thought they’d get millions,” Burbank said. “They got nothing but a giant gray box.”

“We ran the numbers,” said Warrenton Town Councilman Eric Gagnon. “A second Chick-fil-A would’ve brought in more tax revenue — and jobs — than the Amazon data center.”

Gagnon added that these centers don’t generate sales tax like retail businesses. “We did the math,” he said. “A second Chick-fil-A would’ve brought in more consistent revenue than Amazon’s data center. Plus, jobs. Plus, foot traffic. The center? Twenty-five contract workers and a fence.”

Rebecca Bare, a staffer from the Prince William Board of Supervisors, confirmed the risk: “If AWS (Amazon) has a federal contract, you don’t collect anything beyond the land assessment. There is no computer and peripherals tax. Nothing.”

Weir took it further. “In Prince William, we were told we’d get $900 million in revenue from a single data center campus. The real number, after depreciation and exemptions, is more like $100 million — spread out over 25 years.”

Noise, Vibration, and Human Impact

The numbers were disturbing. But the stories about how data centers affect daily life were what truly hit home.

“In Manassas, there’s a neighborhood next to a group of Amazon data centers,” Gagnon said. “People couldn’t sleep in their bedrooms. They moved into their basements. They replaced all their windows. Nothing worked.”

When residents complained, Amazon’s initial fix was to wrap rooftop fans in yoga mats secured with bungee cords. “It didn’t help,” Burbank said. “People were furious.”

Even more concerning, Gagnon said, is a lesser-known problem: low-frequency vibration. “You can’t hear it — you feel it,” he said. “It’s always there. Twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year.”

For residents near proposed sites, the health impacts — from stress and sleep disruption to possible long-term consequences — remain unknown.

And then there’s the psychological toll.

“These buildings change the character of your town,” Burbank said. “They’re massive. Impersonal. They don’t belong in a small historic community.”

Political Pressure and Public Trust

As the meeting continued, the conversation turned to something more familiar but no less frustrating: politics.

“In Warrenton, our town manager helped push through the Amazon data center,” Gagnon said. “Then she left to go work for Amazon. That made people angry.”

He described how the town council approved the project in a narrow 4–3 vote, even after holding back thousands of emails from public review. “They voted to keep them secret. Then, they voted to approve the project. Then, they only shared the emails with themselves. Not the public.”

In Prince William, Supervisor Weir described a campaign of influence, misinformation, and political gamesmanship.

“Prepare to be lied to,” he said. “Not just by the developers. Not just their lawyers. By your own elected officials.”

Weir described how massive campaign contributions flowed into county races — from both parties. “One senator introduced a bill to retroactively lower property taxes for data center landowners — and scheduled a hearing without telling anyone. We killed it. But it never should’ve happened.”

Obsolescence and the Risk of White Elephants

A growing concern, the speakers said, is what happens if — or when — data centers become obsolete.

“This technology is changing fast,” said Gagnon. “There are startups today that can do with a laptop what used to require a building.”

One example is a federal database that used to run on a $39 million data center, which now runs on two Intel mini-PCs stacked together. “And that’s just one company,” Gagnon said. “There are dozens more out there.”

Burbank added, “These buildings aren’t designed for reuse. They’re not like schools you can convert or offices you can remodel. They’re giant concrete shells. Permanent scars.”

Supervisor Weir agreed. “If you’re a co-op or utility, and you’ve built all this infrastructure for data centers — and the centers shut down — you’re stuck. The infrastructure becomes a stranded cost. And guess who pays for it? You.”

What’s the Alternative?

As the discussion shifted toward solutions, a simple but important question came from the audience: If not data centers, then what?

“We’ve got to diversify,” said Gagnon. “In Warrenton, we’re looking at light manufacturing, cold food processing, small startups. Things that bring jobs, bring revenue, and don’t stress the grid or the water table.”

Supervisor Weir added that in Prince William, small contractors are being pushed out as developers buy up industrial-zoned land. “We’re losing plumbers, HVAC companies, warehouse jobs — real people doing real work — and replacing them with server farms that do nothing for the community.”

Gagnon noted that Front Royal, with its highway access and open land, is well-positioned for the right kind of economic development. “Think about what you want to attract. Think about long-term value — not just short-term cash.”

The Fight Ahead

Supervisor Weir didn’t mince words. “Wear your Kevlar,” he said. “This is a knife fight. They will lie. They will outspend you. But if you stay organized — if you hold your ground — you can win.”

As the meeting wound down, Burbank returned to a familiar message: “Get involved.”

She shared the story of a friend who was terrified of public speaking — but still stood up at a key town hearing and made her voice heard. “If she could do it, anyone can,” Burbank said. “You just have to care.”

Gagnon echoed her call. “This isn’t about saying no to everything,” he said. “It’s about deciding what kind of place we want to be. Do we want to preserve the things we love — our quiet, our history, our land — or give it away for a few uncertain dollars?”

And Supervisor Weir didn’t mince words.

“Wear your Kevlar,” he said. “This is a knife fight. They will lie. They will outspend you. But if you stay organized — if you hold your ground — you can win.”

Watch the meeting in this exclusive Royal Examiner video.