Local News

Front Royal, Strasburg cited in wastewater ‘pollution trading’ report

A major pollutant offender – Maryland’s Patapsco Wastewater Treatment Plant – Photo/University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

They’re at it again – the environmental watchdog group that broke the story on excessive levels of e-coli bacteria in the Shenandoah River in April has released a new report on pollution issues in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The November 29 report titled “Sewage and Wastewater Pollution in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed” targets excessive phosphorous emissions from wastewater treatment plants in several states impacting the federally and multi-state protected Chesapeake Bay watershed. The goal of those protections is preservation of the bay’s billion-dollar fishing industry.

Virginia is singled out in the report for a so-called “pollution trading system” which allows wastewater treatment plants to buy and sell pollution credits. And while in theory pollution would remain a “push” (level) as one plant buys excessive pollution rights from another plant, which in turn promises to reduce its pollutant output for the paid credit, the reality is often different according to the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP).

As Royal Examiner reported in late April, the Environmental Integrity Project is a 15-year-old nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, based in Washington D.C. that “is dedicated to enforcing environmental laws and holding polluters and governments accountable to protect public health.” Its executive director is Eric Schaeffer, a former Director of Civil Enforcement at the Environmental Protection Agency.

The new report describes Virginia’s pollution credit process as allowing “wastewater treatment plants in the Chesapeake Bay watershed to engage in pollution trading – a system through which sewage plants can buy the right to pollute more than their permits normally allow.” The system is part of the commonwealth’s 2005 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Nutrient Credit Exchange Program, which includes “a general permit for nutrient trading.”

Under that plan the report observes, “Trades in Virginia must generally be between sewage plants or farms that discharge to the same tributaries. However, some of the tributary-based trading areas are very large – with the Potomac River basin, for example, encompassing the entire Shenandoah River system, as well as all the streams that flow into the Potomac on the distant Northern Neck. This means that trades within a region can cause a worsening in water quality in a local stream, which may already be impaired or threatened by other pollution sources, such as farm runoff, while any benefits of the exchange can be far away.”

“The problem with pollution trading systems is that they can undermine accountability for polluters and create worse contamination in local waterways,” Environmental Integrity Project Executive Director Schaeffer said in a press release accompanying the report. “In theory, these systems are supposed to help the efficiency of the overall Chesapeake Bay cleanup. But in practice, we’ve found they are often poorly designed and can cause more harm than traditional enforcement of individual Clean Water Act permits.”

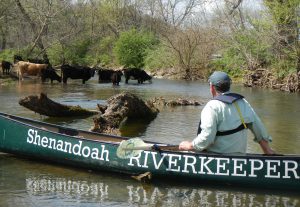

Shenandoah Riverkeeper Mark Frondorf monitored the e-coli situation for April report on status of the Shenandoah. Photo/EIP

EIP’s April 26 report “Water Pollution from Livestock in the Shenandoah Valley” utilized state records to show that more than 90 percent of the water quality monitoring stations in the Shenandoah River and its tributaries over a three-year period (2014 to 2016) detected fecal bacteria (E. coli) at levels deemed unsafe for human contact – with little, if any warning to the public of those levels.

The new Environmental Integrity Project report uses both state and federal records to call into question, among other enforcement issues in multiple states, the pollution trading system’s ultimate impact on the water quality of the Shenandoah River system. It is a river system EIP’s April report documented is already overloaded with phosphorus pollution and algae from farm manure runoff from the livestock industry.

The new report notes that the pollution credit trading system allowed the Front Royal Wastewater Treatment Plant to dump 9,146 pounds of phosphorus into the Shenandoah in 2016, an amount the report stated was more than twice its permitted limit. Virginia’s pollution credit trading system also allowed the Strasburg Sewage Treatment Plant to release 2,942 pounds of phosphorus, more than three times its permitted limit, into the North Fork of the Shenandoah last year – a fork of the Shenandoah already contaminated by excessive levels of phosphorous.

Pictures of mandated upgrade work at Front Royal’s wastewater treatment facility last year, above in March, below in September 2016. Photos/Roger Bianchini

Virginia’s pollution trading system is but one of many state issues reported in the Chesapeake Bay watershed pollution report. Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Delaware and New York get a nod as well.

The report details how Pennsylvania’s pollution credit trading system has been abused to make “transparency nearly impossible.” The report states that Pennsylvania’s wastewater plants “frequently buy credits to allow them to discharge more pollution, but then the plant operators often fail to report this information to an online enforcement database that allows the public and regulators to tell who is following the rules.”

Beyond the issue of pollution trading, EIP’s report reveals that 21 wastewater plants across the Chesapeake Bay watershed have simply violated their permit limits by releasing excessive amounts of nitrogen or phosphorus pollution – and that’s without the cover of a pollution trading system.

Don’t ask me – the Back River WWTP – Photo/Tom Pelton

The report documents 12 Maryland sewage plants, which treat more than half of the state’s wastewater, in violation of their permit limits last year including facilities in Baltimore, Salisbury, Frederick, and Westminster. In West Virginia, six wastewater plants violated their permit limits in 2016; two more in Pennsylvania; and one in New York.

According to the report the largest permit violations in the bay watershed last year came from Baltimore’s Patapsco Wastewater Treatment Plant – the second largest in Maryland – which discharged 3.7 million pounds of nitrogen pollution last year, four times its permit limit – again, that’s without the cover of a pollution trading system. The report adds that by August of this year the Patapsco plant had released more than twice its annually permitted nitrogen.

But not to fear – Maryland Governor Larry Hogan’s administration is expected to release new draft regulations on December 8 to allow pollution trading. One can only wonder if enacted, the new code will be retroactive.

So it seems multiple questions remain: are state regulations cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay to a degree that will save its billion-dollar fishing industry? And if so, is some of that clean up coming at the expense of its tributaries?

Stay tuned, we guess the Environmental Integrity Project will remain on the case, even if the re-tooled Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t. see related story

Attempts to reach Front Royal Town staff on November 28 for information on Town use of the pollution credit trading system; as well as the anticipated impact of completion of $40-million in federal and state-mandated upgrades to its wastewater treatment facility on future participation in that trading system were unsuccessful prior to publication.