Local News

Eastern Influence on Irish Christianity Explored in Work of Local Scholarship

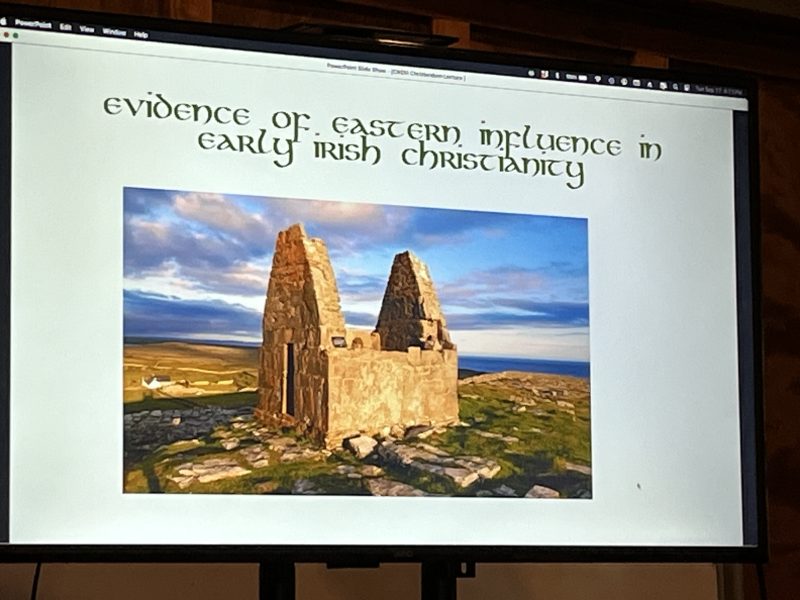

What does a well named after a saint, a beehive hut, and a psalter with a papyrus in the binding have in common? They are all clues leading to the conclusion that Egypt influenced the flowering of Christianity in Ireland and that moreover there is the possibility that St. Patrick was not the first Christian presence in Ireland.

A presentation by author Connie Marshner at Christendom College on her recently published book, Monastery and High Cross: The Forgotten Eastern Roots of Irish Christianity. Royal Examiner Photo Credits: Brenden McHugh.

Author Connie Marshner presented at Christendom College about her recently published book, Monastery and High Cross: The Forgotten Eastern Roots of Irish Christianity. Marshner holds a master’s degree in Gaelic literature and teaches the Gaeilge tongue.

Author Connie Marshner presents to an intimate gathering in St. Kilian’s Café.

In Aghabulloge, County Cork, St. Olan’s Well is located near a stone inscribed in Ogham script with this imperative: “Pray for Olan the Egyptian”. Ogham script is believed by some scholars to have been used as early as the first century C.E. That would possibly put this inscription at a date prior to St. Patrick’s alleged arrival in the fifth century. “Where would the idea come from,” Marshner asks in her book, “that an Egyptian named Olan needed to be prayed for? And that he was a saint? There probably was an Egyptian named Olan, and the folks who didn’t travel more than five miles from home in their lifetime thought he was remarkable and therefore remembered him with respect.” Nobody knows how old the stone is. But there is a school of thought among some scholars that the stone predates Patrick’s arrival by at least a century, thus putting an awareness of Egypt and possibly indicating the latter’s influence among Irish Christians in advance of the fifth century.

And what about the beehive huts on Skellig Michael, an island recently made popular by the Star Wars franchise? These stone-built dwellings made of drystone with a corbelled roof were built by monks to protect themselves from the harsh weather and could have served as places of worship. The only other place where beehive huts were made in this fashion was the deserts of Egypt. Again, a clue. And another clue is the Faddan More psalter, discovered in 2006 by Eddie Fogarty, made in Egyptian style and containing an Egyptian papyrus in the binding. This document dates to the eighth to ninth centuries. “To find a book made the same way,” Marshner writes, “conservators had to go to the binding of the Nag Hammadi codices in Egypt, fourth-century Gnostic Gospels that had been discovered in 1945.” The above are three among a host of artistic, literary, liturgical, and architectural artifacts that illustrate Marshner’s thesis about a strong East-West connection in the development of Irish Christianity and the possibility of a Christian presence in Ireland prior to Patrick’s arrival.

As Nag Hammadi scholarship so richly illustrates, anyone who deals with history is on some level dealing with fiction. That there was a Trojan war is undoubtable but that Homer’s account of it can be treated as scripture is somewhat less certain. The extent to which Irish Christianity is also shrouded in its own telling and retelling is precisely what makes Marshner’s questions so valuable. And it is precisely what makes a new generation of scholars ready to ask those questions so important. A picture emerges of the maritime highway between Egypt and the British Isles, established at least a millennium before Christ, the trade routes on which the savior would travel with his mother to illuminate a world already possessed by an active imagination and forever implant in that imagination the image of a cross. As druids became priests of the church, old ways surrendered to new ways, and in hindsight all history feels providential.

As supplies last, Marshner’s book can be found at Royal Oak Bookshop and ordered on Amazon.