Warren Heritage Society

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History – Virginia’s Eight State Recognized Tribes

Between 2004 and 2009 The Warren Sentinel — Warren County’s newspaper since 1869 — ran a column for the Warren Heritage Society under the heading “Warren’s Heritage.” The column

was most often written by the Society’s executive director, Patrick Farris who occasionally coauthored pieces with the Society archivists during those years: Tom Blumer, Chuck Pomeroy and Judith Pfeiffer.

The column also carried reprints of historical texts composed by Laura Virginia Hale and others, and in general served as a means for educating The Warren Sentinel’s readership on local history and informing the public the Warren Heritage Society’s activities, museums and exhibits.

This series of the Warren’s Heritage Journal is the collection of that five-year column series of the same name. The articles are not organized chronologically, but are assembled thematically, as certain topics of historical interest were revisited over the six years spanning the column’s publication. Each thematic heading appears beneath the Warren’s Heritage heading, collecting together for the reader all articles covering the same topic or set of related topics.

The Warren Heritage Society hope this collection of Warren County history will contribute to the greater awareness and appreciation of the broad and colorful tapestry of the story of Warren County’s past.

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History, Virginia’s Eight State Recognized Tribes

Mattaponi

The Mattaponi and Pamunkey are the only two of the eight state recognized tribes to still have official reservation lands. The Mattaponi reservation is located in King William County along the

Mattaponi River that is the northern boundary of that county. The village of Mattaponi, a clearing in the woods overlooking the Mattaponi River from a cliff, has about 60 residents, although the

tribe’s membership roster has over 450 members. A small museum and cultural programming help maintain the Mattaponi sense of community identity.

One of the most well-known members of the Mattaponi tribe, incidentally, is singer and entertainer Wayne Newton. An interesting feature of the tribe’s name, given to the river of their ancestral home, is that as one traces the origins of the Mattaponi River upstream from King William County, the tributaries of the river become named for syllables of the Mattaponi name. The first division of the river is into the Matta and Poni Rivers in Caroline County and ultimately in Spotsylvania County into the Mat, the Ta, the Po and the Ni Rivers.

Pamunkey

The Pamunkey reservation, also in King William County in a wide bend of the Pamunkey River, is a much larger reservation in acres but has a smaller permanent resident population, as most of the land is bottom land under cultivation. About 32 families live on or own land in the reservation. The Pamunkey Reservation has a museum as well with artifacts recovered from archaeological digs in the area, and on the reservation is the burial place of and monument to the mighty Powhatan, father of the legendary Pocahontas and lord of the Powhatan Confederacy at the dawn of Jamestown’s settlement in the early 1600s. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers meet at the town of West Point at the eastern end of King William County, where they become the York River. Both the Mattaponi and Pamunkey received official state recognition in 1983.

Upper Mattaponi

Closely related to the Mattaponi and Pamunkey are the Upper Mattaponi and Rappahannock tribes, also descended from the Algonquin speaking Powhatan Confederacy and also receiving state recognition in 1983. The Upper Mattaponi are descended from a group of Mattaponi living in the Adamstown area of King William County, where during the early 1700s they had an official British interpreter (by the name of Adams) living amongst them. The Upper Mattaponi incorporated with the state as a tribal entity in 1921, although not receiving state recognition for another 62 years. They do not have a formal reservation but have set aside acreage that serves their community as communally held lands.

Rappahannock

The Rappahannock today, like the Upper Mattaponi, hold a private land trust for their community in lieu of a reservation. In the late 1600s, however, they did briefly have a legally recognized and granted 4000 acre reservation along the Rappahannock River set aside for them by the colonial government, this land being abandoned and ceasing to exist as a separate reservation during disruptive raids by the Iroquois.

The Rappahannock were in Captain John Smith’s time a large and prosperous tribe of the Powhatan Confederacy, occupying 13 known towns along the Rappahannock River. Today’s Rappahannock tribe, recognized in 1983 by the state, is in King and Queen County which lies just north of King William County in between the Mattaponi and Rappahannock Rivers.

Eastern Chickahominy

South of King William County, across the Pamunkey River, are the counties of New Kent and Charles City, homes today to the Eastern Chickahominy and Chickahominy Tribes, respectively. The Eastern Chickahominy are a group of about 150 members who maintain in New Kent County educational and social events for their tribal membership, and received state recognition in 1983. The Eastern Chickahominy consider themselves a division of the Chickahominy, both tribes descending from the Powhatan Confederacy.

Chickahominy

Also receiving state recognition in 1983, the Chickahominy Tribe is centered in Charles City County in between the James River and Chickahominy River, about 25 miles east of Richmond. At one point in the early 1600s the tribe had a treaty obligation with the English colonists to provide soldiers in case of Spanish attack for the defense of Jamestown. The Chickahominy later in the 1600s migrated south of the James River when the colonists at Jamestown began expanding and confiscating more Indian land, but by the 1700s were migrating back to their ancestral home on the north banks of the James and along the Chickahominy River. Today the tribe maintains 25,000 acres of land and has a 750 member community living within a five-mile radius of one another.

Nansemond

The Nansemond Tribe today lives in the cities of Suffolk and Chesapeake (Suffolk City was Nansemond County before 1972). The Nansemond were a tribe of the Powhatan, and very early in the 1600s were driven away from their farmland along the Nansemond River. They held reservation lands in Virginia until 1792, at which point these lands reverted to the state and the Nansemond existed as a community, albeit unorganized, for the next 130 years. In the 1920s the Nansemond reorganized and today claim around 300 tribal members, and are planning a museum on the Nansemond River.

Monacans

The Monacan Indian Nation is the eighth and most recent Native American tribe in Virginia to receive state recognition, earning that officially in 1989. Centered at the community of Bear Mountain in Amherst County, Virginia, south of Charlottesville, the Monacans have a presence historically and still today in the counties of Nelson, Bedford, Albemarle and other adjoining counties. Not of the Algonquin speaking Powhatan, the Siouan speaking Monacan were related and/or allied to the Saponi and Occaneechi of southern Virginia and the Tuscarora of North Carolina. Today’s Saponi and Occaneechi tribes are centered in the northern piedmont of North Carolina and the Tuscarora removed almost completely to New York after loosing the Tuscarora War in 1714. In the 1700s some of the survivors of these marginalized tribes moved to live amongst the Monacans. The Monacans very likely also absorbed the Manahoacs, a tribe reported by John Smith in 1607 to be living along the headwaters of the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers, in what today are the western parts of Rappahannock and Fauquier Counties, bordering Warren County.

The Manahoacs in all probability traversed what is now Warren County — especially to gain access to the Flint Run area of the Fork District, where stone for arrow and spear points was quarried — and quite possibly resided here, making today’s Monacan Indian Nation a descendant population at some level of the original inhabitants of our immediate area. Always distrustful of the English, and living farther west in Virginia than the Powhatan, the Monacans avoided contact when possible with the colonists from their first contact in 1607 with Jamestown explorers to the 1760s, at which time settlement had encroached into every part of their homeland in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge along the James River.

Thomas Jefferson recorded a visit of Monacans to Monticello, the guests paying respects at a cemetery burial mound of their people that had become part of the Jefferson property. Jefferson eventually excavated this mound, acquiring in the process the reputation of being the “Father of Archaeology in America.” During the 1700s some Monacans migrated west or north, but a Monacan community along the upper James River always remained.

The Monacans worked tobacco near Lynchburg for generations in the 1800s, preserving their community identity all the while. In the 1920s Virginia passed laws that prohibited the intermarriage of Indians and Whites, and prohibited Indians from identifying themselves legally as Indians, driving many Monacans away from Virginia with those remaining no longer living as openly as Indians. The modern rebirth of the Monacan Nation is drawing attention to this fascinating Native American community in the heart of Virginia who, since recorded history in Virginia has occupied the same homeland along the upper James River.

Local News

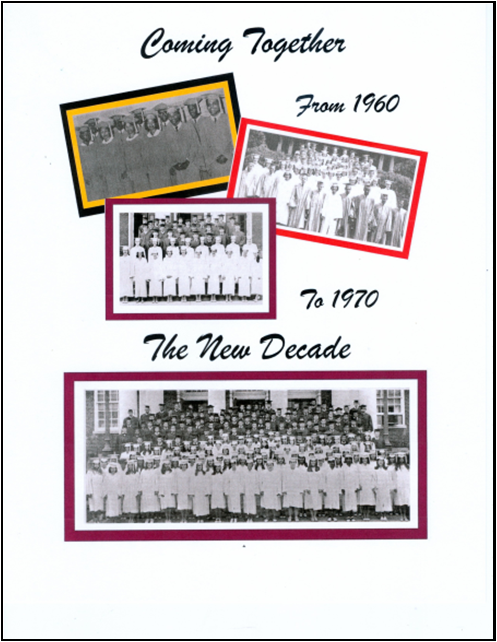

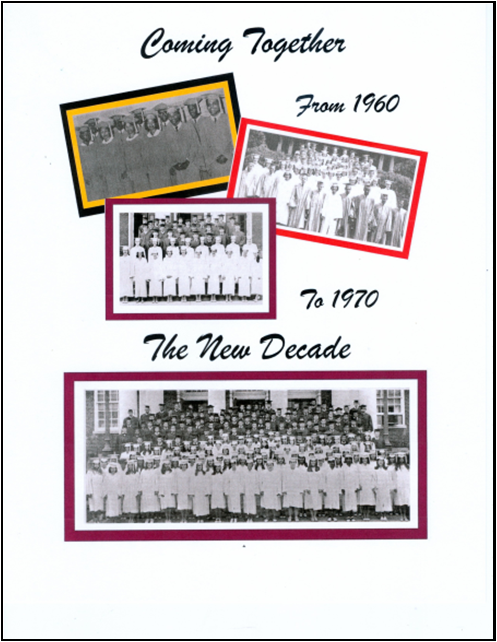

Warren Heritage Society announces the publication of their newest book, “Coming Together”

Coming Together, a pictorial history of the graduating classes from High Schools in Warren County between the years 1959 and 1969.

Warren Heritage Society announces the publication of their newest book, Coming Together, a pictorial history of the graduating classes from High Schools in Warren County between the years 1959 and 1969.

Coming Together is a pictorial history of the graduating classes from the high schools in Warren County between the years 1959 through 1969. The reflections are written by students who graduated from Warren County High School in 1960 and students who graduated from other schools in the area. 1958 opened the door and ushered in a decade of educational change in Warren County. This is the story of the rapid change in secondary education followed by a more gradual change in the entire educational system over the next ten years. In September 1958, Governor Lyndsey Almond closed Warren County High School rather than admit blacks as ordered by the courts. The term “massive resistance” became the catch phrase for what happened that day. The book covers all the students’ experiences in Warren County High School, Criser High School and Mosby Academy.

In addition to the history of the period, the book also includes photos of the students and school buildings, each school’s song, mascot, school color and photos of student activities. There are also Memorial Pages for classmates lost over the years.

Coming Together is available for purchase at the Warren Heritage Society Gift Shop (101 Chester Street, Front Royal, VA 22630) by calling (540) 636-1446 or email whsivylodge@comcast.net. The price is $25 or $30 if mailed.

Community Events

Send bracelets to quarantined residents of Commonwealth Assisted Living in Front Royal through WeAreSPACE.org

Join us in giving our beloved local elders a tangible reminder that they are NOT alone, and we’re in this together. Visit www.wearespace.org/shop — choose “Gift for Elderly” and your bracelet order will be shipped to residents at Commonwealth Assisted Living in Front Royal, Virginia.

While we can’t go visit our elders, give a hug to the immuno-compromised and homeless, or make Personal Protection Equipment magically appear, we CAN send a symbol of our love, hope and solidarity to those feeling most alone and unsupported in these times. Liz Gibbs of SPACE, has adopted Commonwealth Assisted Living in Front Royal as a partner recipient of online orders of “We’re in this Together” bracelets. Join us in reminding local shut-in elderly that they are not alone by sending a lovely bracelet as a tangible reminder.

The bracelets are made out of recycled paper beads that are hand-rolled, one by one, by refugee women in Kampala, Uganda. Beyond financial opportunity, the bead creation serves as a meditative, therapeutic outlet for the women. They are then strung by the aunties and uncles of the Light Up Life Maisha Home, a home for orphans and vulnerable children in Kampala, Uganda. Their salary supports the home’s expenses including food and school fees for the children. “I’m so thankful that Liz joined me on my trip to Uganda in October 2019 and fell in love with the Light up Life family. She has taught me the value of supporting them through empowerment, not merely charity” says Beth Medved Waller of Liz’s Space Bracelet efforts which employ the volunteers of Light up Life. “Purchasing a bracelet is an ultimate win-win in that it helps support children in Uganda, warms the heart of strangers and friends who receive them, and can be a tangible daily reminder on our own wrists that we are truly all in this together, especially now,” she added.

HOW YOU CAN SUPPORT

- Shop: Select a Unity Bracelet Gift – the charm reads “We’re In This Together.”

- Checkout: Choose your Shipping Location – send to yourself, a specified recipient or have us deliver to one of our target populations through our partner organizations (all “Gift to Elderly” orders will be sent to Commonwealth Assisted Living until each resident has a bracelet)

- Pay: Choose your price – We, like other small businesses, are trying to make ends meet in this time. That being said, we don’t want financial worries to stop your generosity. Use code LOVE50 for 50% off your order if you need it. Because, you guessed it…we’re in this together.

- Celebrate: Smile big – you just made someone’s day and gave them a reminder that they are never alone – a gift they will be able to treasure even after this crisis has passed.

ABOUT SPACE:

SPACE PROMOTES COLLECTIVE INDIVIDUALISM BY SUPPORTING INDIVIDUALS TO CATALYZE COLLECTIVE CHANGE… Our products, starting with the paper bead bracelets, embody our values of empowerment and unity. The bracelets are handmade by refugee artisans and caretakers of vulnerable children in Kampala, Uganda and marketed/distributed by women in America. This project gives us the opportunity to put our skills to work and create financial freedom to support ourselves, our families and our community. The bracelets further empower every person who wears one to believe that they can create a new world, starting with themselves.

Every time you look at your bracelet, you can be reminded that:

- You made an environmentally positive decision by purchasing a product that is recycled and repurposed.

- You made a socially positive decision by purchasing a product that empowers refugee women and caretakers of vulnerable children.

- You made a spiritually positive decision by purchasing a product that supports unity, joy and the celebration of our shared humanity.

To make a purchase or a tax-deductible donation, please visit www.wearespace.org

WHAT MATTERS INITIATIVE

Are you or your group in need of a free video that could be created to help market your cause or event? Beth’s WHAT MATTERS Warren videos post on Facebook and YouTube.

Learn more Beth’s nonprofit, WHAT MATTERS, a 501 (c) (3), at www.whatmattersw2.com – check out the “Community” section to request a TOWN TIP or WHAT MATTERS WARREN BETHvid or contact her at 540-671-6145 or beth@whatmattersw2.com.

About WHAT MATTERS:

WHAT MATTERS is a 501(c)(3) that focuses on local and global outreach to help spread the word, support and raise funds for causes that matter (primarily through Facebook). WHAT MATTERS has ZERO overhead as 100% of the expenses are funded by Beth’s real estate business thanks to her clients and supporters. Every cent raised goes to the cause she’s promoting and most are matched by Beth. If you’d like to get involved, or travel to Africa with her on a future trip to work with the children of Light up Life Foundations, please visit www.whatmattersw2.com.

Warren Heritage Society

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History-Part 10

The month we’ll recall the long record of Virginia’s past that predates the settlement of Jamestown — an event which will dominate discussions of all things historical throughout 2007 here in Virginia.

The history of the Commonwealth of Virginia is a long and storied one. One of the Old Dominion’s other nicknames, “Mother of the Colonies,” reminds us that when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock they were settling lands still a part of Virginia. As we approach the four hundred year anniversary of the founding of Virginia, what, then, could augment this long and fascinating story even more? The answer lies in the history of those who stood at the shores of Virginia before it was known by that name, and watched and greeted the arriving settlers. The Native American peoples of Virginia, as all Native Americans, would become a part of the fabric of America’s history, their presence upon the land that was once theirs alone still echoes in the names of countless rivers and streams, mountains and valleys.

The colonial settlers of Virginia and Native peoples of Virginia had complex relations from the beginning of recorded history. Very often blood was shed, the Powhatan Confederacy alone

fighting three wars with the encroaching colonists in an attempt to maintain their lands, their sovereignty, and their way of life. Treaties were drafted between these two groups — sometimes honored, often ignored. The ever-increasing stream of colonists and the agricultural and urban infrastructures they created, in addition to the diseases that arrived with them from the Old World, meant that by the settlement of the Shenandoah Valley in the late 1720s colonists found the Great Valley all but devoid of a Native presence. Some settlers assumed that the Valley had never been occupied before, but this was a misleading and incorrect assumption, as the Native American presence in Warren County and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was ancient, and had only been disrupted shortly prior to settlement of The Valley.

The Native Americans of the area of North America that would become modern-day Virginia spoke multiple dialects — often confined to individual villages or collections of villages — but that came from one of three distinct language groups: Algonquian (spoken by the Powhatan), Iroquoian (spoken by the Cherokee), and Siouan (spoken by the Monocans and Manahoacs, the two tribes that lived closest to and in the Shenandoah Valley in the 1600s). The area that is now Virginia was part of the Eastern Woodlands cultural zone in North America, the trademarks of which by the 1500s included corn and bean agriculture, hunting, fishing, trapping and stable village life (village sites being permanent or semi-permanent within a given area of control). Native peoples in the eastern woodlands cultivated tobacco for ritual use, had elaborate and complex political, social, artistic and spiritual lives, and were far from the “savages” that Europeans would often see and portray them as being. They built permanent ceremonial centers and established trade networks that stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Their ways of life before the European colonization did make some serious changes to the continent; for instance, by the 1500s most large animal species living in eastern North America had been made extinct through over-hunting.

In the late 1400s explorers following the lead of Christopher Columbus traveled along the eastern seaboard of North America, mapping the continent and beginning a tradition that would last a century of farther exploration and of European fishing vessels coming to fish the waters of eastern North America without establishing permanent settlements. By the late 1500s, however, this had changed in two dramatic ways. The first serious incursion into the Southeast occurred with the expedition of Spanish conquistador Hernando De Soto, who led a small army from Florida though what is now the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Texas (some historians feel the route could have come all the way north into Virginia).

This expedition exposed Native Americans in the Southeast to many diseases to which they had never before been exposed, including smallpox, measles, bubonic plague, typhus and influenza. Archaeologists working on the remains of village sites from this period of first contact routinely discover the death rate from these new diseases to be around 90%, with most victims dying within a few weeks’ time of initial infection (this would be the modern-day equivalent of Virginia’s current population of over seven million people being reduced to a few hundred thousand). The De Soto expedition brought violent contact between colonists and Native Americans to the Southeast as well. De Soto regularly ordered his attack dogs to maul captive Native Americans to death in order to frighten local populations, and took hostages to guarantee his group’s safe passage through North America’s interior.

The results from expeditions such as these were twofold; first, Native peoples had to reorganize their devastated communities that had been so reduced in population that many villages were abandoned and whole groups of people were displaced from their ancestral homes, and second, Native peoples of the southeast became very wary and defensive of European explorers in general. It is no wonder given this early contact that when the Spanish built a mission in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay in 1570 that it lasted only one year before the entire mission was slaughtered.

The Spanish mission to the Chesapeake Bay — an attempt to convert Native Americans and extend their colonization of the eastern seaboard – had ended in a massacre of the mission in 1571, but the English claim to North America as of yet also lacked a presence on the ground, and the Spanish were preparing for war with the English This is the environment into which Sir Walter Raleigh’s famous Roanoke Island settlement attempts were made in the 1580s.

A part of England’s Virginia claim in the 1500s, Roanoke Island is today in North Carolina, and has come to be known in American history as the “Lost Colony” (one of the colony’s internal explorative expeditions came by river into what is now Southside Virginia around 1581). Raleigh’s agents demanded the Native peoples supply their colony with food and sometimes killed Native leaders as a means of intimidating surrounding villages. When the Spanish Armada’s attempted invasion of England stalled Raleigh’s resupply efforts for almost two years, the colonists were never seen or heard from again.

After the 1607 founding of Jamestown an attempt was made to locate these people, but it was unsuccessful except in giving the impression that the colonists had disbanded and the survivors intermarried with the area’s Native peoples. 1607 was a watershed year for Native peoples of Virginia and the Southeast, as the small contingent of Europeans that made their way to the Chesapeake Bay stayed on permanently this time despite dying off in large numbers annually from malaria, malnutrition and warfare. Virginia — the colony — began to grow irrevocably into the lands of Virginia’s Native population, who coped in a variety of ways.

One method of coping was to fight. The Algonquian speaking Powhatan Confederacy under Chiefs Powhatan and later Opechancanough famously made war on the English, then peace, then war — and the English responded in kind, sometimes making their contacts peaceably, sometimes through burning Powhatan villages. The Powhatan under Opechancanough on March 22, 1622 attacked the colonists in Virginia, killing at least 10% of the entire settler population in one day, but the English kept immigrating and the conflict’s resolution became a matter of time, as every year more and more people streamed into Virginia from Europe and Africa.

Other methods of coping with the colonization of their homelands were for Native peoples to acculturate to the new language and ways of the settler, or to remove themselves physically and attempt to find shelter farther west from colonial expansion. By the former method, many Native peoples became part of the general population, forming communities isolated from other Virginians (this generally occurred along the colony’s borderlands, such as with the Occoneechi, Saponi and Nansemond who lived and still live between Virginia and North Carolina and the Shawnee who came to settle briefly in the Shenandoah Valley) or intermarrying within colonial society. By the mid-1700s Native peoples in Virginia east of the Blue Ridge were almost entirely English-speaking, had adopted the farmstead in place of the village, become Protestant Christians of one denomination or another, dressed as the English colonists and were generally indistinguishable from them except for their physical appearance. By the latter method, many of Virginia’s Native peoples pushed on into the mountains of what is now West Virginia (where the Melungeon heritage, as Appalachian communities of Native American ancestry-have become known, still has a very strong presence today), the Shawnee withdrawing to Indiana by the 1760s and the Cherokee to Tennessee by the 1790s.

By the mid to late 1600s the Powhatan villages were generally making a reluctant peace and permanent accommodation with the colonists. Into our collective past went the story of Powhatan’s famous daughter Pocahontas, whose life experiences have become an important part of Virginia history. Today two descendant groups of the Powhatan Confederacy occupy reservations in Virginia — the Mattaponi and Pamunkey of King William County (located in Tidewater, Virginia, an hour east of Richmond). Recognized by Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1658, these are the oldest Indian Reservations in what has become the United States. Whereas the “Praying Towns” created by the New England colonists for the purpose of converting the Native peoples of that area were similar in that they confined certain groups of people to certain lands, Praying Towns were small villages without political independence. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey, however, have since 1646 upheld a treaty with the governor of Virginia in order to maintain their ancestral lands. On the fourth Wednesday of every November (for 349 years by 2005) the Mattaponi and Pamunkey present wild game as gifts to the governor of Virginia — and if this ceremony sounds familiar it is worth remembering that Virginia experienced the first official celebration of Thanksgiving, well before New Englanders began making this a habit.

Warren Heritage Society

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History-Part 9

Those of us fortunate to have known Rebecca Poe will not be surprised at all by the fact that the depth and breadth of her research and documentation into local history was such that today we are still benefiting from and discovering her contributions. Today I would like to share a rediscovery, of sorts, unearthed by Assistant Archivist Judy Pfeiffer in the Laura Virginia Hale Archives. While combing through materials in preparation for the mounting of the Warren Heritage Society’s newest exhibit, entitled “Native Warren,” Judy came across an article printed almost two decades ago in the Warren Sentinel by Becky Poe during her long tenure at the Sentinel.

Concerning the old cemetery at Reliance, a community in the northwest corner of the county between Success and Confidence (no kidding), Becky documented the existence of a unique grave set in the middle of the cemetery for an unknown Native American who had lived in Reliance at the turn of the century.

The modern story began in the 1960s when a rural mail carrier learned through an elderly lady living on the Guard Hill portion his route that an Indian was buried in the Old Providence Church graveyard in Reliance. The woman had always heard that he was buried between two of her relatives, that he had lived in Reliance but had also lived in Rockland, and that no one remembered his name or how or when he died — just that he had been an Indian.

When the mail carrier brought this information to the attention of Gary Elswick, a local historian and trustee of the Old Providence Cemetery at the time, Elswick followed up on the lead and discovered a simple, unmarked, square concrete headstone located between the graves of two members of the Rosenberry family. No name or dates appeared on the headstone, but the two graves framing this marker were for folks who passed away between 1892 and 1907. This fact in addition to the material composition of the marker — concrete — leads to a general conclusion that the person interred beneath may have died around the late 1800s or early 1900s.

A man living in Reliance in the 1960s named Jesse James Vanderpool, also an American Indian, made with Els wick’s permission a cold-hammered copper plate with the image of a Native American man’s profile. The small plate was affixed to the gravestone and remains to this day a reminder of the man interred within the otherwise unmarked and undocumented grave.

Warren Heritage Society

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History-Part 8

We conclude this week with our series on Native American History and Heritage based on the Warren Heritage Society’s newest exhibit on that topic with a reminder of Native Virginians’ at points

of crises, during Bacon’s Rebellion, Indian Removal, and the era of eugenics.

Bacon’s Rebellion: Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675 was a stark example of the belief many European settlers held that theirs was a superior culture and true faith, giving them the right to confiscate Native American land. There were many causes for Bacon’s Rebellion: tobacco prices were declining, bad weather made agriculture less profitable, and rising prices in the English market were lowering profits in Virginia.

In this tense environment, poor relations with the Indians resulted in confusion and ultimately a naked attempt by some colonists to seize Indian lands. When the Doeg Tribe attacked a plantation, the colonists retaliated against the wrong tribe, resulting in many Native American raids on the colonists. The Governor at the time, William Berkeley, made a critical error when he coordinated a meeting between the parties that resulted in the chiefs of many tribes being murdered. In an attempt to organize a peace, Governor Berkeley tried to convince the English that the Native Americans were friendly and loyal. At this point a colonist, Nathaniel Bacon, took it upon himself to organize an attack against all Native peoples along Virginia’s frontier. He stoked up disdain against Governor Berkeley because of Berkeley’s perceived defense of the Native Americans. Bacon led attacks against many innocent Native peoples, disobeying the governor’s orders to the contrary, leaving Berkeley no choice but to label Bacon a rebel.

Berkeley reported to Bacon that if he gave himself up, he would send him back to England to be tried by the courts of King Charles II. Bacon refused this offer of an English trial, and the fight between Berkley and Bacon continued until Bacon obtained enough supporters to force Berkeley from power. Bacon died suddenly at this point in the conflict, and Berkeley regained control of the troubled colony.

Indian Removal: Thomas Jefferson was an early believer in the idea that Native Americans should be coerced into adopting the European culture and Christian faith. Although Jefferson was curious about Native American culture, he held to the ethnocentric beliefs common in his own time period, and felt that in order to prevent the land east of the Mississippi from ever being taken by French or British, he had to rid it of Native Americans. He therefore created an Indian Removal Act during his administration (1801-1809) which served as a model for future President Andrew Jackson who, against the judgment of Congress and the Supreme Court, pursued his Indian Removal policies ruthlessly in the 1830s.

The Legacy of Walter Plecker: In 1924, Walter Plecker influenced the General Assembly to pass the Racial Integrity Law in Virginia. This law stated that in the cases of marriage, birth, and death, there were only two races: White and Black. He also instructed that there be no Native American allowed in white or black schools or churches. This law left no records of or for Native Americans,

extinguishing Native American identity from the legal and governmental perspectives. Native Americans in Virginia were left to create their own schools and churches, however, these schools only

went through the 7th grade, following which Native Americans students had to leave the state in order to further their education. In the 1960s, the Civil Rights movements allowed more job and

educational opportunities for Native Americans. Finally in 1982, the “Commission of Indians” was formed in Virginia to study and research the Indians of Virginia.

Today there are 8 recognized tribes in Virginia: Chickahominy Indian Tribe in Charles City County; Chickahominy Indian Tribe, Eastern Division in New Kent County; Monacan Indian Tribe in Amherst County; Nansemond Indian Tribal Association in the City of Chesapeake; Rappahannock Indian Tribe in Essex, Caroline, and King & Queen Counties; Pamunkey Tribes in King William County; Mattaponi Tribe in King William County; and the Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe in King William County.

Warren Heritage Society

Warren’s Heritage: Native American History-Part 7

We continue this week with our series on Native American History and Heritage based on the Warren Heritage Society’s exhibit on that topic with a look at the differing perspectives of the colonists and the Powhatan peoples at the dawn of colonization in Virginia.

The Colonists’ Perspective: Throughout the study of Colonial America, many historians have researched and theorized the preconceptions and misconceptions that the first settler had about the Native Americans, and many interesting theories have surfaced out of this research. For example, some historians believe that the Europeans thought the Indian way of life was similar to their own old life ways from their Anglo-Saxon ancestry. Many English believed that England’s money-hungry ways had corrupted what was once good in English culture, and there existed in English society a naive desire to return to those supposedly traditional ways. These fed the Englishmen’s belief that since the Indians mimicked the pre-modern English way of life that the Indians, with a litde persuasion, would be easily “civilized.” Other historians found that, although at first apprehensive about taking Indian land, the first colonists justified this seizure by believing that the English could provide the Indians with access to European culture, which from the English perspective was far superior to Indian Society. The first colonists believed it would be easy to persuade the Indians to adapt to the European culture, as they felt the Indians, too, would see the culture of the colonists as superior. Ethnohistorians feel that because these cultural misconceptions between the first setders of Virginia and the Natives of Virginia were never resolved, it caused unnecessary destruction throughout the 1600s for both the setders and the Native American tribes.

The Native Perspective: According to ethnohistorians, in 1607 when the first setders arrived they believed that the Native Americans were not as organized or as powerful as the colonists. Werowocomoco Wahunsonacook Powhatan, known in commonly as Powhatan, had by that time extended dominion over many Algonquian tribes in the territory known as Tsenacommacah, now central Tidewater Virginia. Rival tribes not under his influence worried him more than did the first English setders and their attempt at a permanent colony. Another reason Wahunsonacook was not that concerned about the newcomers and could not see them as a clear threat was the vast cultural difference; the English subsistence strategies did not remotely resemble the Natives’ way of practicing such basic tasks as fishing, hunting, or clearing fields, leading Wahunsonacook and others to believe that the English were an inferior race.

This view changed, however, when the adventurers turned into settlers and began constructing James Fort. This was seen as a threat to Wahunsonacook, and on May 26, 1607, he attacked the colony. Although it was not a large-scale attack, it did frighten both sides; the Native Americans learned about the effectiveness of the English guns, and the English learned about the Native Americans’ skill and ability to orchestrate large and sudden attacks. As time went on the attacks continued, and the first Powhatan War erupted. Both the English and the Native peoples suffered tremendously throughout the war, and both sides would continue to suffer in part because they refused to understand each other. Wahunsonacook always believed that providing the English with gifts would lure the English in as allies and that the English would help protect him from his rivals — not in fact become his largest rival. The English never understood Wahunsonacook’s diplomacy with them, because they had their own motives in creating an economically profitable colony.

The English maintained a belief that their superior culture would simply be adopted by the Native Americans, and make them into acculturated Christians. When the Native Americans did not cooperate, the English used force. Therefore, the European misconception that the Native Americans would soon “come to their senses” and transform into Europeans cost many lives on both sides, and continued the turmoil.

In the 1600s, the Powhatan of Virginia were forced to make yearly payments to the Colonial government. All land between the Black Water and York Rivers was lost, and by 1677 the remainder of the Coastal Indian’s land was lost. The Coastal tribes were sectioned off into small reservations. In the 1700s, the English decided that the Indians should be taught Christianity. Many viewed it their duty to God to convert the Native peoples to Christianity, whether the Native Americans liked it or not. Some of the Native people succumbed to or freely adopted the Christian faith, while others fought to retain their cultural and religious beliefs and traditions.

Although it may appear that Native Americans and their cultures were completely overrun by the Europeans, it is important to understand that the European Empires, colonies, and ultimately the new nations of the Americas were developed and shaped by the Native peoples of the New World. When early settlers arrived they had to learn Native American etiquette in situations of trade, and also relied heavily upon Native American guides to survive. Perhaps the most important thing to understand about the Native Americans’ influence on the development of America is the fact that the French and English, in attempts to claim land from one and another, desperately needed the alliances of Native American groups.